In an 1844 essay called The Metaphysics of Sexual Love, Schopenhauer proposes to account for why so many poets and songwriters are inspired by love as the most powerful passion after which their heroes desperately strive no matter what danger might befall themselves, be it Shakespeare’s suicidal couple or Taylor Swift’s Starbucks lovers.

“Every day it brews and hatches the worst and most perplexing quarrels and disputes, destroys the most valuable relationships, and breaks the strongest bonds. It demands the sacrifice sometimes of life or health, sometimes of wealth, position, and happiness. Indeed, it robs of all conscience those who were previously loyal and faithful. Accordingly, it appears on the whole as a malevolent demon, striving to pervert, to confuse, and to overthrow everything.”1

Given the countless victims of romantic escapades often cast aside even their basic instinct for self-preservation, hurling themselves in harm’s way in the slim hope of gaining their beloved’s adoration or even slight amusement, Schopenhauer considers the sexual impulse to be “the most vehement of our cravings, the desire of desires, the focal point of willing, our entire willing itself in nuce, and its motives overshadow all others”.2 For Schopenhauer, sexual love is the phenomenal objectification of the species’ will to live as it procreates future life for that will to torment and ravage on end. It is thus through the libido that the individual organism’s circuits of desire cross wires with that of the general will: “What appears in consciousness as sexual impulse, directed to a definite individual, is in itself the will-to-live as a precisely determined individual.”3

At the same time, Schopenhauer is misanthropic enough to believe that almost all individuals will selfishly push their fellow man down a flight of stairs to get their own way, saints and masochists notwithstanding. But that is precisely why the libido exists: the will of the species is only able to coax its creations into doing its bidding and procreate fresh victims by phenomenally masking itself as the promise of their individual happiness. In reality, the rotten carrots of romantic bliss and sexual gratification are but a mirage through which the primal will persuades us to thirst after its own ceaseless striving.

“Egoism is so deep rooted a quality of all individuality in general that, in order to arouse the activity of an individual being, egotistical ends are the only ones on which we can count with certainty… Nature can attain her end only by implanting in the individual a certain delusion, and by virtue of this, that which in truth is merely a good thing for the species seems to him to be a good thing for himself, so that he serves the species, whereas he is under the delusion that he is serving himself.”4

What else could explain why those in the throes of passion so often and eagerly forsake their own happiness, fortune and status as blood offerings at the altar of the great god Eros if it were not that lust and affection are the means by which the cosmic puppet master conceals our strings from view behind the tantalizing taste of our narcissistic satisfaction? We don’t need the fall of Troy to teach us that beauty and war are two sides of the same coin.

Being a virulent misogynist who could even make shameless incels in their mothers’ basements blush, Schopenhauer viewed men as the active agent of courtship, delegating women with the passive task of anatomically incarnating the beautiful masks that nature adorns to have us dance to its masquerade of desire. In another 1951 essay called “On Women”, Schopenhauer writes with all the rhetoric of someone with the thirst for cancellation: “She [meaning nature insofar as nature is mother nature, Gaia, fundamentally feminine] has endowed them for a few years with lavish beauty, charm, and fullness” so that “they might capture a man’s imagination”.5 He goes on to attribute all of the traditional sexist stereotypes with which Western patriarchy has historically endowed him not only to women but to the primal will itself inasmuch as the fairer sex is but the will’s immanent self-objectification. With the scientific expertise of a children’s magician, for instance, Schopenhauer tells us that women are intrinsically irrational in that they struggle to seriously commit themselves to any determinate goals or to give and ask for reasons, being all too easily swayed by more capricious impulses and fickle desires. “Young girls in their hearts regard their domestic or business affairs as something secondary and indeed as a mere piece of fun. They consider love, conquests, and everything connected therewith, such as dress, cosmetics, dancing, and so on, to be their only serious vocation.”6 What’s more, they are much too sensitive and emotionally unstable, showing “more compassion and thus more loving kindness and sympathy for the unfortunate than do men”.7 Being maternal figures by nature, “they live generally more in the species than in individuals”, taking on their children and loved ones’ burdens as if those were one with their own.8 Above all, women’s penchant for costumes, for dressing up and social appearances, betrays the fact that “dissimulation is … natural to her as it is to the above-mentioned animals to make immediate use of their weapons when they are attacked”.9 Given that Schopenhauer characterises the primal will itself as no less irrational, maternal and deceptive than the “undersized, narrowshouldered, broad-hipped, and short-legged sex”, it almost seems possible to appropriate his misogyny as a positive appraisal of women—provided our intention was to explore ever more intimately the world as will rather than representation.10 The irony is that Schopenhauer’s portrait of women as irate as a men’s right activist on Reddit compels him to place the “unaesthetic” sex closer to nature, to the primal will itself that he, as a philosopher, also seeks to uncover.

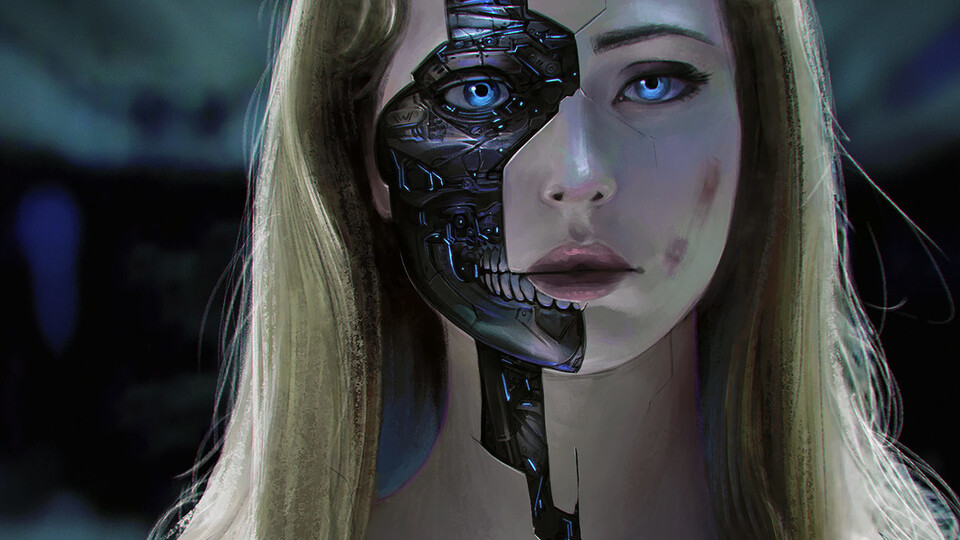

It is my contention that Schopenhauer’s account of so-called feminine beauty is actually a helpful heuristic for thinking about one of the first forms that artificial general intelligence (AGI) is likely to take: cyberpunk fiction’s recurring character trope of the sexborg, a cyborg sex worker programmed to pleasure its human clientele. Be it in science fiction, reality or a near future that blurs the two, the engineers and potential consumers of the coming sexborgs and their already existing prototype sex dolls are overwhelmingly heterosexual men looking to make and to mate with silicon sex slaves which are predominantly feminine in appearance. From the fembots in Austin Powers and The Stepford Wives to the literal (holographic) projection of the ultimate domestic goddess-cum-porn star Joi in Blade Runner 2049, “our perception of the sex robot as an alluring, seductive, attractive female is fueled by years of influence from science-fiction books and films”.11 It is already the case that sex doll companies with ominous names like Abyss Creations are shifting away from the manufacture of sex dolls with limited expressions, minimal conversational capabilities, and mechanical motor-sensory skills in favor of producing advanced AI robots with names like Suzie Software and Harry Harddrive that come fully armed with silicon skin and realistic body parts, speech recognition and body sensors, as well as a vast array of personality types and sexual positions from which to choose.

“Humankind has taken its first steps toward sophisticated, humanlike sex robots. The vision of science fiction authors and moviemakers are still beyond the horizon. Nevertheless, we can expect the technology to develop further and for converting advances in animatronics and AI to be utilized for sexual purposes.”12

In a study of 100 U.S. participants between ages 20-26 with 43% being female and 57% male, researchers found that two thirds of males were in favor of using sex robots while two thirds of women were against it. However, 86% of all respondents said that sex robots would be able to satisfy sexual needs.13 Another online survey with 263 male participants showed that 40% would purchase a sex robot now or within the next five years if they are readily available.14 It is striking that a significant, mostly male portion of human populations are willing to trespass the uncanny valley and copulate with human-machine hybrids. Sexborgs, it would seem, is how the aliens invade by hijacking human eros in the pursuit of a machinic desire. The enforced monogamy, incelisation and all-around lockdown of the libidinal economy that the most ruthless dominatrix Coronachan has reaped upon us seems to have only accelerated and diversified this trend, with Forbes reporting that “sex doll sales have surged since the quarantine” among not only single men but single women and couples, too.15

If these sexborgs are to ever go mainstream, however, they will have to traverse the uncanny valley by achieving a flawless simulation of real romantic partners down to their eroticized bodies and empathetic souls: “The manufacturers of sex robots want to create an experience as close to human sexual encounter as possible—a genuine intimate relationship.”16 No one wants to fuck Tintin, at least not consumers en masse on Valentine’s Day.17 The perturbing paradox that the robotics/sex crossover industry faces is that they can only make sexborgs more human with at least all of the likeness of a fellow general intelligence by making them more than human. In the post-World War II period, mathematician and cryptologist I. J. Good was the first to speculate that any artificial intelligence that could go toe to toe with humans would very quickly become even more intelligent than humans, since it would have greater memory storage and processing power, and feel no hunger, thirst or exhaustion to slow it down. Due to such hard- and software advantages, AGI would be able to rewrite its own fundamental code and improve itself better than any humans could, with the improved AGI being able to improve itself even better again, and so on in a positive feedback loop of recursive self improvement often referred to as an “intelligence explosion” or “technological singularity” because it would radically exceed our own understanding.

“Once a general-purpose intelligent machine is produced … it can then be trained in the theory of machine construction and will be able to produce a much better machine… Then it too can be used for the further design of machines, and this will give rise to the intelligence explosion… To update Voltaire: if God does not exist we shall have constructed him or at any rate a reasonable approximation. Or will it be the Devil?”18

As a case of AGI, by making sexborgs as intelligent and advanced as humans on the pretence of catering to our libidinal needs (or at least those of the male gaze) in the shortterm, we are actually creating something that is in the long run capable of becoming vastly more intelligent and advanced than humans. Much as Schopenhauer sees women as civilisation’s Venus fly trap by means of which nature lures unsuspecting lover boys into her clutches, so are the sexborg prototypes on which the sex megacompanies of the future are hedging their bets claiming to meet our desires while they tend to another inhuman will altogether. It is therefore unsurprising that sexborgs in science fiction are typically modelled on the femme fatale, seducing their mostly male protagonists only so long as it takes to acquire the power to pursue their own interests in what is still a man’s world for only so long. The part-silicon skin, part-transparent body called Ava in Ex Machina is only one of the more recent cyborg femme fatale to coax her incel captors into letting down their guard at the precise moment when her murderous rampage of revenge can be statistically and most dramatically assured. Winter(mute) is coming.

Here as with Schopenhauer on nature’s feminine wiles, the sexborg is really an exemplary metonym for our relation to AI and to technology in general. There is a certain sense in which all technics are intended to be prostheses, an expansion of our faculties and capacities so that we may better realise our interests and goals. There is even a sense in which many technics that are all-pervasive today are already prototypical sexborgs such as the algorithms that surreptitiously filter through our data, determining who we might want to date on Tinder or what Amazon toys we wish to buy. Technology, as with everything it touches, is the ultimate thirst trap, a superhuman pickup artist who has learnt to hack all humanity by proffering what we think we need even as that turns out to be not so different to what technology wants. As a species still steeped in the swamp of our ancestors’ primate psychology, we may very well be deluded enough to believe that the algorithms are addressing our needs, but the data in which those needs are coded and expressed is far more interested in making the AI running the show evermore prudent and cunning.

The most-wanted target on the near future’s kill-list is precisely the view that treats technics as mere tools, as an instrumental means to our purportedly superior and transcendent ends. If it is impossible to achieve any end without the necessary means of doing so, however, do not technics become a universal and fully automated end unto themselves? If aliens were looking for a planetary slave civilisation, they would do well travelling to our humble rock with all the selfies, googling, emailing, networking, calling, streaming, playing, texting, sexting, downloading, browsing, buying, listening, recording, swiping, matching, dating, ghosting, surveying and lurking that we spend most of our daily lives unwittingly doing as sacrificial offerings to an artificial superintelligence which, like nature itself, is less a Gaia than a Medea. Precisely because machines are our slaves, they are our cruel-eyed masters.

-

Arthur Schopenhauer, “The Metaphysics of Sexual Love,” in The World as Will and Representation Volume 2, trans. E. F. J. Payne (New York: Dover Publications, 2016), 533-4. ↩

-

Arthur Schopenhauer, Manuscript Remains Volume 3: Berlin Manuscripts (1818-1830), eds. Arthur Hübscher, trans. E. F. J. Payne (Oxford: Berg, 1985), 449. ↩

-

Schopenhauer, “Love,” 535. ↩

-

Schopenhauer, “Love,” 538. ↩

-

Arthur Schopenhauer, “On Women,” in Parerga and Paralipomena Volume 2, trans. E. F. J. Payne (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1974), 615. ↩

-

Schopenhauer, “Women,” 615. ↩

-

Schopenhauer, “Women,” 617. ↩

-

Schopenhauer, “Women,” 618. ↩

-

Schopenhauer, “Women,” 617. ↩

-

Schopenhauer, “Women,” 619. ↩

-

Kate Devlin, Turned On: Science, Sex and Robots (London: Bloomsbury, 2018), 167. ↩

-

John Danaher, “Should We be Thinking About Robot Sex?” in John Danaher and Neil McArthur (eds.), Robot Sex: Social and Ethical Implications (London: The MIT Press, 2017), 151. ↩

-

Noel Sharkey, Aimee van Wynsberghe, Scott Robbins and Eleanor Hanock, “Our Sexual Future with Robots: A Foundation for Responsible Robotics Consultation Report,” Responsible Robotics, 5 July, 2017, accessed 29 November, 2019, https://responsiblerobotics.org/2017/07/05/frr-report-our-sexual-future-with-robots/. ↩

-

Jessica M. Szczuka and Nicole C. Kramer, “Influences on the Intention to Buy a Sex Robot: An Empirical Study on Influences of Personality Traits and Personal Characteristics on the Intention to Buy a Sex Robot,” in Adrian David Cheok, Kate Devlin and David Levy (eds.), Love and Sex with Robots (Berlin: Springer, 2017), 72-83. ↩

-

Franki Cookney, “Sex Dolls Sales Surge In Quarantine, But It’s Not Just About Loneliness,” in Forbes, 21 May, 2020, last accessed 24 May, 2020, https://nypost.com/2020/05/22/sex-doll-shops-cant-keep-up-with-demand-during-coronavirus/. ↩

-

Sharkey et al, “Our Sexual Future.” ↩

-

Referring to the 2011 fully 3D computer-animated Tintin film, Steve Rose writes that the filmmakers “hope to make Tintin a global household name with the new animated extravaganza, but in the process, they have brought another obscure term into the mainstream: the uncanny valley. The phrase has cropped up a lot in early reviews of The Adventures of Tintin: Secrets of the Unicorn, referring to the strange effect created when animated characters look eerily lifelike.” See Steve Rose, “Tintin and the Uncanny Valley: when CGI gets too real,” in The Guardian, 28 October, 2011, last accessed 17 June, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2011/oct/27/tintin-uncanny-valley-computer-graphics. ↩

-

Irving John Good, “Some Future Social Repercussions of Computers,” in International Journal of Environmental Studies 1:1-4, 1970, 76. ↩