When Michael Jackson died on the 25th of June 2009, we were convinced that it was a publicity stunt. During his funeral service, held at the Staples Centre in L.A., we kept expecting him to emerge from the coffin, dance on his own grave and shock us all back to life. We were only children then but we knew something very special and very strange had left the Earth.

One could say many things about Michael. But I will say only this: He was the first person to live in the 21st century. Many living today will never live in the 21st century. They may appear very modern and have very modern views, wear modern clothes and talk about modern things, but they are 20th century people through and through. Michael Jackson was the first person to leave the 20th century. And for that he was crucified.

Michael as Philosophical Model

In the 1980s one of the favourite pastimes of cultural theorists was to write about Michael Jackson. This was the heyday of Semiotext(e) in the USA and Art and Text in Australia. Theorists wrote essays with titles like “The Meaning and Multiplicity of the Body of Michael Jackson”, full of references to signifiers, symbolic economies and libidinal excess. In short, things which seem a little passé to the scholars of today.

But one man exceeded all others in writing about Michael. That man was Jean Baudrillard. Baudrillard differed from these other writers, first and foremost because he had style. And only a stylist can recognise his own.

For Baudrillard, Michael was more than a symptom of this or that element of late capitalism. Michael was our destiny. With his trademark verve, Baudrillard outlined a genealogy of “extreme phenomena”, creating a pantheon which included the porn star Ciccolina, the pop star Madonna and Michael who were all, “genetically baroque beings whose erotic look conceals their generic lack of specificity”.1

But Michael’s angelic universality is singled out for special treatment:

“Michael Jackson is a solitary mutant, a precursor of a hybridization that is perfect because it is universal—the race to end all races. Today’s young people have no problem with a miscegenated society: they already inhabit such a universe, and Michael Jackson foreshadows what they see as an ideal future. Add to this the fact that Michael has had his face lifted, his hair straightened, his skin lightened—in short, he has been reconstructed with the greatest attention to detail.”2

What strikes us first about Baudrillard’s analysis is the care he takes to maintain a zero-degree of language. When discussing these “extreme phenomena”, he seeks to avoid the condemnation and violence that was done to Michael by the philosophers, which in many ways mirrored his horrific treatment by the press. What interests Baudrillard is a new formation of identity, one which is no longer tied to archetypical 20th century obsessions like race, class or gender but is instead technological through and through.

Baudrillard continues in a palpably religious mode:

“This is what makes him such an innocent and pure child—the artificial hermaphrodite of the fable, better able even than Christ to reign over the world and reconcile its contradictions; better than a child-god because he is child-prosthesis, an embryo of all those dreamt-of mutations that will deliver us from race and sex.”3

It is a curious passage and one which needs to be investigated further. It is perhaps difficult for us today, who have been lethally infected by Netflix and its campaign to paint Michael as a sadistic paedophile, to reconstruct this sense of his innocence and purity.4

Firstly, what is a child-prosthesis?

We can understand this in relation to Michael’s insistence that as a boy he was exploited by his father Joe Jackson. These included an obsessive performance practice regime, severe beatings and a constant tirade of insults about Michael’s appearance, particularly his nose. But Michael’s notorious doctor Conrad Murray takes the story further. He claims that Michael received injections of puberty-blockers to ensure he retained his piercing falsetto. It is akin to the tradition of the castrato in Christian choral music, the boys whose testicles were removed so that they could continue singing in the angelic register of childhood long after their bodies had entered adulthood. Jackson thus remained in a state of artificial temporal suspension, in other words a chemically castrated childhood. Innocence, it appears, can be synthesised.

And what then is “the artificial hermaphrodite of the fable” that Baudrillard refers to? There are a scores of stories of seraphic androgynes with unbelievable artistic talents. The most famous modern tale is Zola’s Sarrasine (1830). It tells the story of a young sculptor, Sarrasine who falls in love with a beautiful opera singer, Zambinella. When he finally meets her, he is “astonished at the reserve [she] maintained toward him” and her insistence on an ascetic affair.

“Ah, you would not love me as I long to be loved.”

“How can you say that?”

“Not to satisfy any vulgar passion; purely.”5

But Sarrasine the sculptor cannot sublimate his desires into his art. He wants to make love to his muse. He finds out too late that she is a castrato, the product of the Church’s bizarre erotico-musical fantasias. When he turns on her with accusations, he is stabbed to death by the Cardinal’s men who stand guard over this celestial voice.

This tale, which was analysed by Roland Barthes in his masterpiece S/Z (1973), is a kind of precursor to the life of Michael, who would become an icon of beauty and asceticism for Baudrillard. Michael was something he could not stop writing about, something pure and yet terrifyingly seductive. It is a question then of the relation between technology, asceticism and art.

Michael as Artistic Model

Just as the philosophers longed to make Michael over in their own image so too did the artists of the 1980s. Keith Haring, in a page from his scintillating journals expresses this fascination:

“I talk about my respect for Michael’s attempts to take creation in his own hands and invent a non-black, non-white, non-male, non-female creature by utilising plastic surgery and modern technology. He’s totally Walt-Disneyed out! … He’s denied the finality of God’s creation and taken it into his own hands, while all the time parading around in front of American pop culture. I think it would be much cooler if he would go all the way and get his ears pointed or add a tail or something, but give him time!”6

In many ways Haring seems to echo Baudrillard with his concerns for a completely plastic post-racial and post-gender self-construction through andro-technics.

There are two essential notes to draw out here. Firstly, Michael is understood as a model for a kind of artistic life, a way of living one’s life as a total artwork. He has, “denied the finality of God’s creation and taken it into his own hands”. In other words, he embodies one of the Promethean antinomies of the avant-garde that underscored 20th century aesthetic discourse.7 Given that God was dead and creation was radically unfinished, it was now the role of the artistic worker to take up where the dead divinity had left off. This was understood canonically as both a form of self-stylisation and an approach to creation in which life and art were indistinguishable. First Duchamp, then Cahun, now Michael.

Secondly, we must attend to Haring’s ecstatic remark that Michael is “totally Walt-Disneyed out!” In other words, he is a force of the cartoon-made-man. The Disneyfication of social reality, as argued by Audrey Schmidt in her penetrating analysis of Fantasia 2000, represents the triumph of the “pantheistic and inhuman forces” of capital which “produce not dread, but the thrill of being taken, subjected, consumed … turning that fear and loss of control into exhilarating fun”.8 Was this not one of the charms of Haring’s own work, which rigorously pursued, in poetry, graffiti and print-making a total cartoonification of social life in which the compulsive pictorialism of capital was given a sexy and jazzy ambiance?

Yet Haring was not the only doyenne of downtown New York to draw on Michael’s cartoon creativity. We are perhaps familiar with Jeff Koons’ life-size porcelain sculpture Michael Jackson and Bubbles (1988) made as part of his “Banality” series. Against those who wish to make art an academic exercise in social critique, Koons insists on, “Banality as saviour”.9 He states in a wonderful interview with Norman Rosenthal, “I was using banality to communicate that the things we have in our history are perfect. No matter what they are they’re perfect… It’s our past and it’s our being, the things that we respond to, and they’re perfect. And I used it to remove judgement and to remove the type of hierarchy that exists.”10

For Koons, Jackson is an avatar of a non-pejorative expressive banality. What Baudrillard described as his “generic lack of specificity”, his perfection and his universality is for Koons a model for a radical aesthetic equality of a distinctly post-Enlightenment kind. That is, of one not based on aesthetic judgement but a total affirmation of self and world. He goes on to provide a remarkable formalist reading of his sculpture:

“When I made Michael Jackson and Bubbles I was thinking of Renaissance sculpture instead of antiquity. Michael Jackson and Bubbles has a triangular-shape that is the same as Michelangelo’s Pietá [1488-9]. It does also make reference to Egyptian sculpture—it’s a little bit King Tut, and the way the leg comes up makes a pyramid, and the body makes another pyramid. So you have the three Pyramids of Giza there. But it is more of a reference to Renaissance sculpture.”11

For Koons it is a question of communicability and faith. Art had reached a dead-end in the politicised conceptualism of the late 70s, which was involved in elaborate in-jokes for those in-the-know, that is, others who had been educated in exclusive art schools.

Jackson was a model for Koons because “he would do absolutely anything that was necessary to be able to communicate with people”. This was precisely what the Renaissance sculptors like Michelangelo had done, in their works which adorned Churches where everyday people could worship and give dignity to their daily lives. Michael in Koons’s evangelical eyes is both a Medici, in his lavish property at the Neverland Ranch, and himself a living Michelangelo. But he is a dancing sculpture whose lithe elegance would grace television screens all over the world. The dream of a universal language, cherished by 20th century avant-gardists but long since abandoned was invoked by Koons who understood it as the inheritor of the Renaissance ideal of a unification between art, humanity and the state.

The Koonsian Michael is thus a force of idealisation and joy as millions attempted to recreate the Moonwalk and impersonate his extra-terrestrial anti-gravity. It was this element of Jackson’s command over movement which would, much later inspire Isa Genzken in her collage painting Wind (2009) and her sculpture Clothesline (Dedicated to Michael Jackson) (2010). Like Koons, when asked about this dedication Genzken replied defiantly in her Berlinese monotone, “I Love Michael Jackson”.

Yet the reference to Egypt is intriguing too. The pyramidal structures inside the Koonsian sculpture would give fuel to conspiracists who sought to link Koons to Satanism and paedophilia, in an early anticipation of Qanonist neo-paranoia. But if one can see past these accusations it is not too much of a stretch to consider another universalist and Egyptophile, G.W.F. Hegel as anticipating Michael’s symbolic strength. Hegel argued, following Herodotus, that the Egyptians were “the first people to put forward the doctrine of the immortality of the soul”.12 The spirit thus externalises itself for the first time as “interiority” which is epitomised by the Pyramids, the “prototype of symbolical art”. The Pyramids were “prodigious crystals which conceal in themselves an inner meaning”.13 In other words, they are Necropoli designed to house dead souls.

But for Hegel Egyptian interiority lacked the independence, freedom and life of the genuine spirit, which would be realised in Greek sculpture. The spirit of Egyptian art for Hegel could only express itself symbolically and the Pyramid was the frozen monument of spirit at a stand-still. The Memnon Colossi of Amenhotep III, had “no freedom of movement” and those figures which surrounded it were “without grace and living movement”.14

Had not Michael overcome an ancient aesthetic problem? He was pure symbol and yet he was also a person. He was a sculpture, but one imbued with the spirit of absolute movement. He had a heart and a soul and yet was not the prisoner of the pyramidal body. Michael took the flesh into his own hands and sculpted it in a way that Hegel could only ever dream of. Michael was the spirit of plasticity incarnate. The Geist which walked on Moons. Here, was the possibility of true freedom—the freedom to transfigure one’s body in line with one’s wildest artistic dreams. And he transformed himself for us, the public, who would feast on his every move and hang off his every word.

Enter the 21st Century

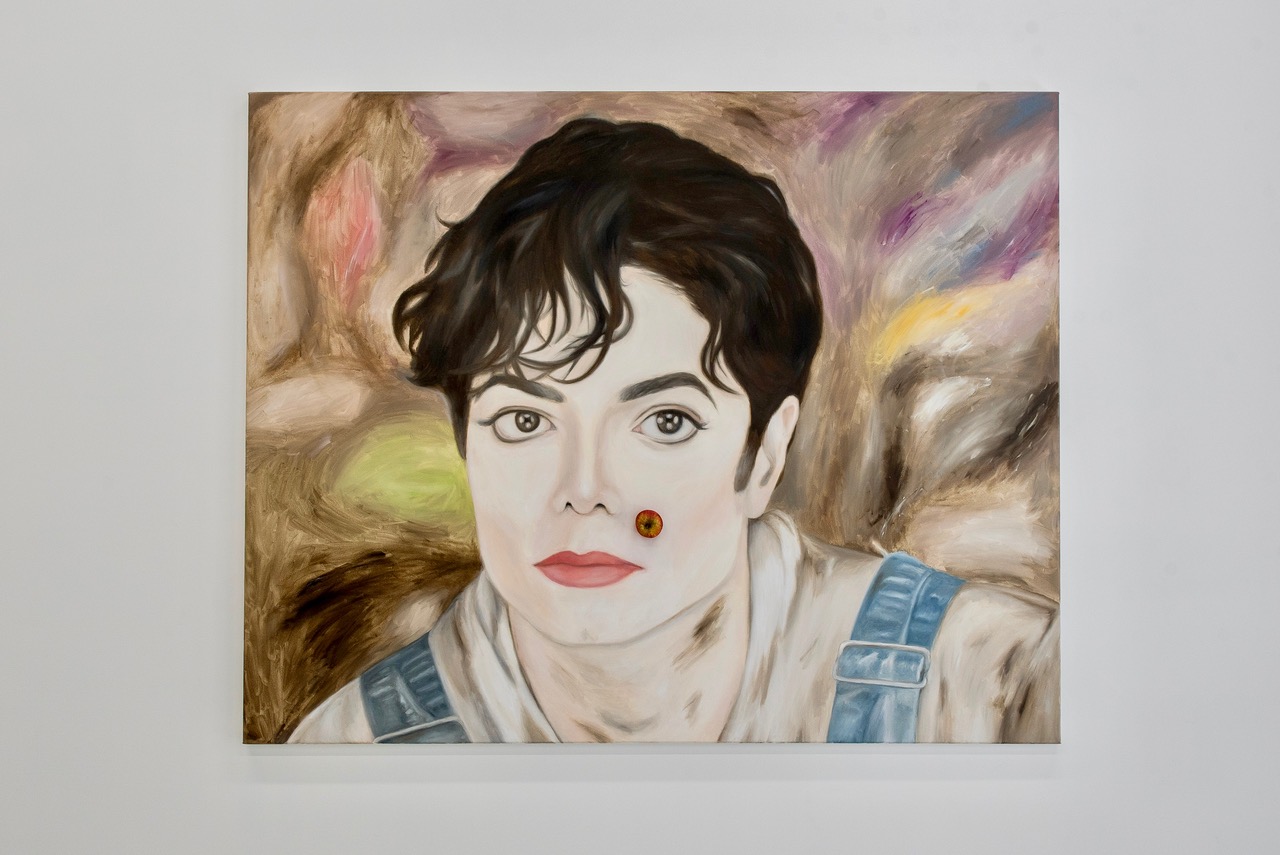

Buoyed by Koonsian excess we float into the 21st century. In a gallery in Melbourne, Australia, a painting of Michael is displayed. The painting is by the supremely talented young artist Billy Coulthurst and is entitled, Michael as Marilyn With French Apple (2021). The painting was displayed as part of Propagé curated by Carmen-Sibha Keiso which opened at TCB on the 30th of June, 2021.

Alas, stranded in Adelaide, the images of the painting first reached me online. I had already read with excitement Vincent Le’s catalogue essay for Coulthurst’s earlier show that year Earth is Healing at Meow2 which, in a tone of marvellous bombast, exclaimed: “Constant change is nothing new. We all feel alienated and unnatural again, nature is healing!”15 Le was riffing on that earlier exhibition’s title, which echoed the memetic phrase, “Nature is Healing” that had come to stand for the joy many of us felt in the early months of the Covidian era.

The nature which Le was referring to was not merely the trees and grasslands that had benefited from the momentary economic ceasefire caused by the brief halt in transport circulation. Le was invoking the quasi-natural process of creative destruction, theorised by the Austrian economist Joseph Alois Schumpeter who argued that capitalism could ceaselessly evolve and transfigure itself to meet new challenges and obstacles. For Le, Coulthurst’s work was one such creative response to what was happening around us. While others bemoaned the rash of Covidian art which glutted our screens, Le saw in Coulthurst’s deliciously decadent oil paintings an act of invention akin to the birth of a new industry. To those who struggled to accept the Covidian, Coulthurstian painting seemed to shrug its shoulders, and, with an easy but refined virtuosity, continue blithely on.

Yet why had Coulthurst painted Michael in the first place? And why had he painted him as Marilyn? Michael attended the 1991 Academy Awards with Madonna. Watching on television Baudrillard must have soiled his immaculate French trousers. The event was a coming out of sorts, as the duo had been secret friends since the early 1980s when both were at the height of their fame. They had even attempted to collaborate on Michael’s 1991 hit “In the Closet” but Jackson’s notorious perfectionism made this impossible.

On that day in March ‘91, it was as if Madonna had been reading Baudrillard’s recent writings as she arrived on the red carpet dressed as Marilyn Monroe, engaging in an elaborate game of simulacral stylistics. Michael was obsessed with Marilyn. He even owned a print of a rare photograph of her with Bobbie Kennedy and JFK, one of the few that was not destroyed by the FBI. In this photograph, which Jackson treasured, Marilyn was still wearing the famous pink Rhinestone gown after delivering her infamous rendition of “Happy Birthday Mr. President” to JFK on May 19, 1962. The image is as dark as those that emerged from Neverland when it was searched by Police in 2003.

Yet Coulthurst’s painting has a laidback detachment, an almost Californian coolness, which purifies it of these rather dark political and aesthetic histories. It is as if he is asking us to see Michael for the first time. And crucial to this is the small resin “French Apple”, a beauty spot, which gives the work its title. Marilyn accentuated her own beauty spot with dark makeup. Here Coulthurst accentuates Michael’s own uncanny capacity for universality. In this way he is part of a tradition, the one I have sketched—Baudrillard, Haring, Koons, Genzken and now Coulthurst.

When we meditate on Michael we do not merely meditate on celebrity. This would be too cheap, too easy. Instead, when we meditate on Michael as he emerges from Coulhurst’s neo-psychedelic palette we meditate on the possibility of our own beauty. Of the beauty of those who are longing to leave behind the 20th century, with its chokehold of rigorously policed identities and its breathless spiritual narcosis.

When we meditate on Michael as he is painted by Coulhurst we breathe in deeply and slowly. We pause and then we meditate on the possibility of movement. Moving through time. Moving through space. Moving through a dancefloor. Moving with oil paint. A seemingly outdated medium, but one which, having taught us to taste eternity before, once more frees us to love Michael Jackson again, the way we did when we were little children.

Michael was the first person to live in the 21st century. And for that he was crucified. For that, he will remain forever ours.

Adelaide, 12th of April, 2022.

-

Jean Baudrillard, “Transsexuality”, The Transparency of Evil (London: Verso, 1990), 21. ↩

-

Baudrillard, “Transsexuality”, 21. ↩

-

Baudrillard, “Transsexuality”, 22 ↩

-

See Leaving Neverland: Michael Jackson and Me dir. Dan Reed, HBO, 2019. ↩

-

Honoré de Balzac, Sarrasine (1830) in Roland Barthes, S/Z (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1974), 246. ↩

-

Keith Haring. Keith Haring’s Journals. (London: Viking Penguin, 1996), 179. ↩

-

Peter Bürger, The Theory of the Avant-Garde (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1974), 50. ↩

-

Audrey Schmidt “Happy Endings: Disney Accelerationism”, Splm: Society for the Propagation of Libidinal Materialism (Footscray: Docs on Call, 2021), 53. ↩

-

Jeff Koons, Jeff Koons Conversations With Norman Rosenthal (London: Thames & Hudson, 2014), 140. ↩

-

Koons, Jeff Koons Conversations, 140 ↩

-

Koons, Jeff Koons Converations, 145 ↩

-

G.W.F. Hegel, “The Development of the Ideal into the Particular Forms of Art: Part One The Symbolic Form of Art” Aesthetics: Lectures on Fine Art (Oxford: Clarendon Press), 355. ↩

-

Hegel, “The Symbolic Form of Art”, Aesthetics, 356. ↩

-

Hegel, “The Symbolic Form of Art”, Aesthetics, 360. ↩

-

Vincent Le, “Earth is Healing” (2021) https://meow2gallery.com/. ↩