Has the Communist Party of China declared war on the androgyne?

A series of new policies were launched by the Chinese state in 2021 to combat decadent influences on the youth of the nation. The policy that received the most attention internationally was a limit on gaming time for minors, reducing playtime to the hours of 8-9pm on weekends and public holidays.

These restrictions are part of a wider attempt by the Communist Party to regulate the Chinese digital economy which had already targeted companies such as the e-commerce platform Alibaba and the gaming and social media giant Tencent for violations of anti-monopoly laws earlier that year. China’s gaming industry is, unsurprisingly, the largest in the world and the regulation of addictive gaming was received by foreign correspondents with a mixture of confusion and disdain.

But there was another curious element in the recent round of restrictions. Namely, the focus on the problem of effeminate men. In an editorial, the state news organ Xinhua noted that, “obscene and violent content and those breeding unhealthy tendencies, such as money-worship and effeminacy should be removed”.

Xinhua was particularly scornful of what it termed niang pao (娘炮, or “sissy pants”, male stars who dominate the Chinese mediascape. From the genre of danmei (耽美) or “boys love” TV shows such as The Untamed (2019), to the popularity of K-pop and its cult of fresh male idols, the androgyne known more affectionately as xiao xian rou (小鲜肉), or “little fresh meat”, is at the heart of the Chinese entertainment industry.

It is not the first time a critique of effeminacy has been issued by the CCP. The 13th Five Year plan launched in 2016, sought to “study the influence of the phenomenon of internet celebrities on youth values and countermeasures.” A pseudonymous article was issued by Xinhua in 2018 condemning an increasingly effeminate masculinity, in particular the popularity of male cosmetics and beauty products. In 2019 the ear lobes of a number of male stars including Jing Boran (井柏然) were blurred to conceal piercings, inadvertently transforming the ear into a captivating fetish.

Western commentators were eager to deride the sissyphobic Communist Party and its hetero-masculinist rhetoric. Was this directive merely a message to appease the old red guard of the Party? Or is something else afoot in this condemnation of the beautiful boys of China?

Xiao Xian Rou and the Pop Idol Conspiracy

An intriguing article on the xiao xian rou was published by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in 2019. Entitled “Do you know how hard the CIA is working to get you to love effeminate stars?” the article propounded an elaborate conspiracy linking the rise in androgynous males in East Asian pop culture to the United States and its psychological war machine.

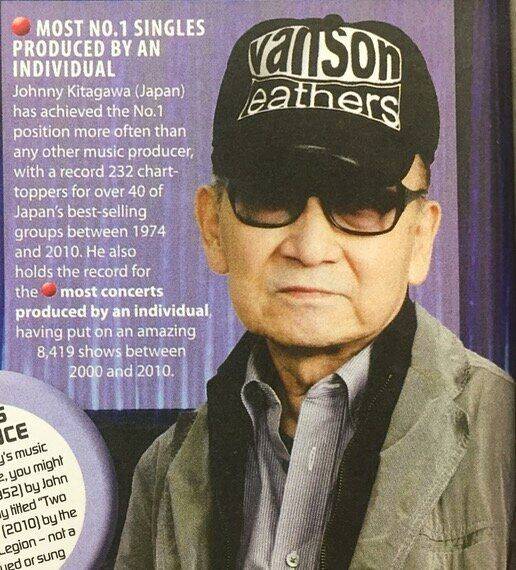

The story goes like this: the attempt to undermine the masculinity of twenty-first century China is the continuation of a US psyop beginning in occupied post-war Japan. In order to prevent the return of Japanese Imperial might, the CIA funded the work of Japanese-American musical impresario Johnny Kitagawa, who launched a series of successful boy bands and is widely regarded as the father of J-Pop.

Beginning in the 1960s with The Johnnies, Kitagawa’s talent agency Johnny & Associates developed the blueprint for the multi-billion-dollar industry of idol groups in Asia. According to this theory it is no wonder that Yukio Mishima’s attempt to revive the bushido code and stage an aristocratic body-building revolution failed so pathetically. His neo-traditionalism was no match for the power of undercover American androtechnical pop warfare.

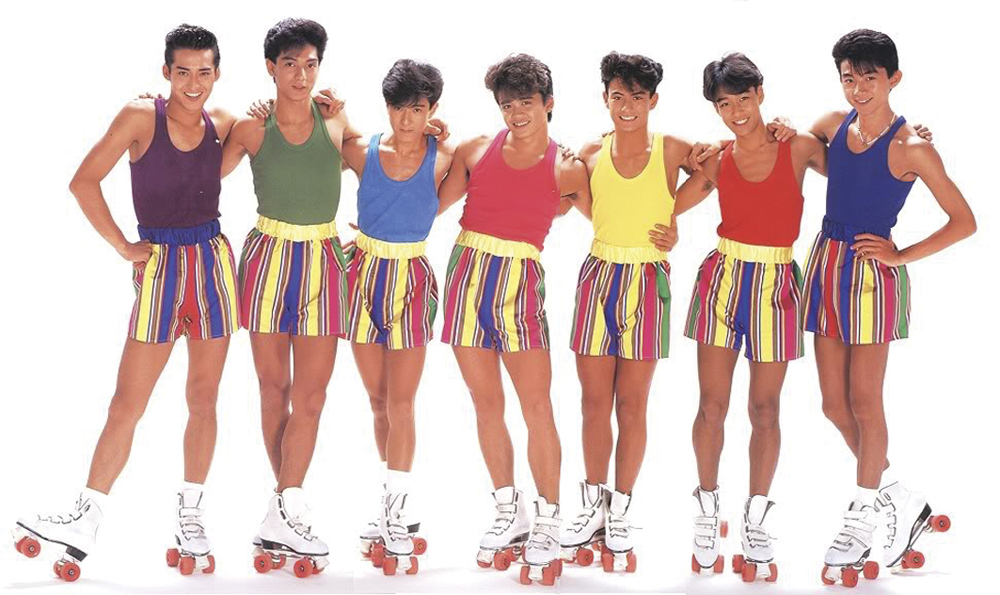

Kitagawa held talent quests to recruit teenage boys who would then become part of a pool of artists known as Johnny’s Juniors. The boys would move into the company dormitory and were educated in the company school. This education involved grueling singing, acting, dance training and, perhaps most importantly, lessons in personal grooming. The Johnny’s, as they came to be known, were characterised by their youthful androgynous beauty and were at the heart of the rise of the bishōnen or “beautiful boy” archetype which swept through manga, anime and cinema in the 1970s.

Kitagawa’s eye for male beauty and his legendary mesmeric powers of control eventually led to accusations of paedophilia, charges which were eventually dropped but they had already tarnished his reputation in the Japanese entertainment industry. By this time the bishōnen had taken on a life of its own. The androgyne was now an unstoppable force within East Asian pop culture.

The Kitagawa model for the idol economy accelerated in the twenty-first century. Anyone familiar with the current wave of K-Pop stars will note the familiarity between Kitagawa’s industrial production of androtechnical male beauty and the current regimes of Korean pop companies such as Big Hit Entertainment who engineered the BTS phenomenon.

The hallyu (韓流) or Korean wave achieved its first international success within China and led to the formation of a number of copy-cat Chinese groups like TFBOYS and Luna, whose members have gone on to star in countless films and TV shows and who have now been recruited as potent brand ambassadors.

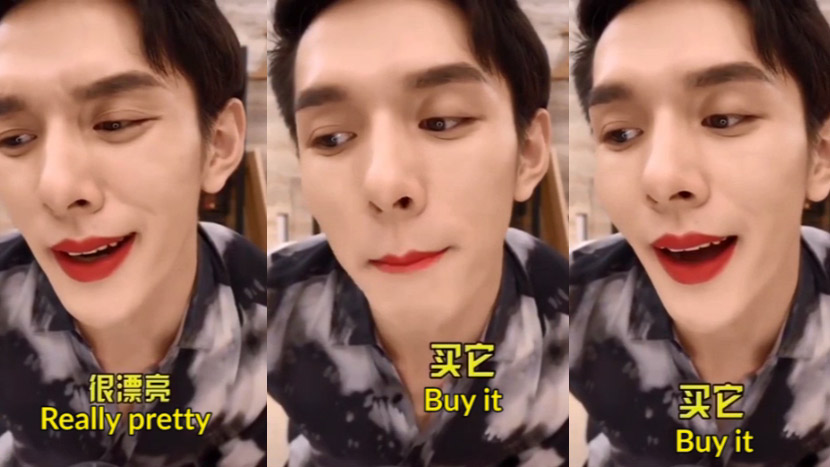

The fan economy which accompanies this androgynous aesthetic is a multi-billion-dollar industry. The xiao xian rou is thus a new form of consumer, attuned to luxury street wear and male cosmetics, which is one of the fastest growing consumer markets in China. For example, in 2019 lipstick promoted by Li Jiaqi (李佳琦) an archetypal xiao xian rou, sold 15,000 units in under five minutes on Single’s Day (光棍节), a festival of consumption designed as an equivalent to Valentine’s Day.

The report from the Academy of Social Sciences argues that the feminisation of Chinese men is an attempt by the CIA to engineer a weak Chinese male, addicted to pop idols, online shopping and skincare regimes and thus utterly incapable of defending the nation from attack.

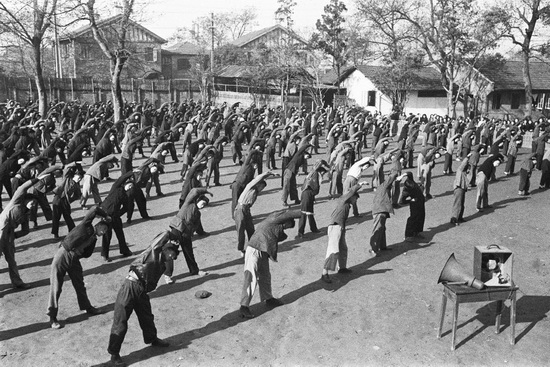

Even if this report is merely a piece of anti-US propaganda there has been a renewed focus on physical education in Chinese schools and in the last five years around 20,000 new PE teachers have been trained through free teacher training programs. But there is a much longer history to the fear of an effeminate China which takes us back to the very dawn of the formation of the great People’s Republic.

Training the Sick Man of Asia

The very first publication by a young Mao Zedong was entitled “A Study of Physical Education” and dates from 1917. In the essay the future father of modern China writes:

“Our Nation is wanting in strength. The military spirit has not been encouraged: the physical condition of the population deteriorates daily. This is an extremely disturbing phenomenon.”1

The young Mao criticises what he perceives to be the feudal regime’s overemphasis on scholarship and literary accomplishment at the expense of physical education. Instead, the future leader advocates passionately for strengthening programs, including exercising in the nude.

Mao’s interest in physical education is part of a wider historical transformation, in what philosopher Peter Sloterdijk describes as the evolution of asceticism into “practicing regimes” in the late 19th and early 20th century.

“The cult of sport that exploded around 1900 possesses an outstanding intellectual-historical, or rather ethical-historical and asceticism-historical, significance, as it demonstrates an epochal change of emphasis in practice behaviour—a transformation best described as a re-somatisation or de-spiritualisation of asceticisms.” 2

The “de-spiritualisation of asceticism” was apparent in the mass engagement with physical culture and athleticism which was to become a hallmark of Maoist China and its mass outdoor calisthenics programs.

Mao’s call for a national program of physical strengthening expressed a wider cultural mood. The connection between physical degeneration and political inefficacy were central to the writing of many modern Chinese intellectuals. The military officer and scholar, Yan Fu (严复) (1854-1921), was the first to describe China as the “sick man of Asia”, in response to the nation’s defeat in the first Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95. He asked the question: “Does not contemporary China resemble a sick man?”3

Yan Fu’s thinking was influenced by Social Darwinian thought and he is now best remembered for his translation of the works of Darwin, Thomas Huxley and Herbert Spencer. Hence, while the trope of China as a “sick man” is often discussed in relation to orientalist fears of contamination by European commentators, the trope was central to critiques offered by modern Chinese reformers.

One example of the trope of illness is the writing of journalist Liang Qichao (梁啓超) (1873-1929), and his work On the New Citizen (he was chief editor of New Citizen Journal) (1903-1905). Drawing on Western diagnoses of China’s sickness he writes,

“Our nation is known throughout the world as a sick man (bìngfū 病夫), and is viewed as paralysed and having completely lost its powers of resistance. Throughout the East and West, there is not one country that is not eagerly sharpening its knives and waiting to dish us up like fish meat.”4

Liang then provides a historical genealogy of Chinese infirmity with its roots in a tradition of scholarly overrefinement.

“China was known to all under heaven for its refined and effete (wēnruò 温弱) qualities, and its disease of timidity has penetrated deeply into its core. When even the fierce and valiant man were assimilated by us, they too became infected (chuanran 传染) with this disease (bing 病), thereby becoming weak and completely losing their fierce disposition.”5

The American sinologist Carlos Rojas notes, in his analysis of Liang’s writing that wenruo consists of characters connoting “cultivated”, “effete”, “weak” or “frail”. He notes the manner in which wen designates cultural attainment such as literary accomplishment, which was contrasted with wu, or martial valour.6 For Liang, like Mao, China’s martial prowess or lack thereof had deeper historical origins which could be traced back to Imperial Chinese literati culture and its criterion of ostensibly effeminate values. Hence, we too must travel further back in time to meet these infamous scholar-poets and psycho-spiritual alchemists.

Effeminate Literati and Spiritual Androgynisation

The question of effeminacy and literati culture is a difficult topic to broach in a brief report such as this. Nonetheless, we can note the way in which the literati of different periods contributed to redefining gender dynamics within Chinese culture more broadly.

The Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) has been identified as a crucial period in the formation of literati gender ambiguity. The period witnessed the flowering of what Chinese literary historian Zuyan Zhou (周组炎) describes as a veritable “androgyny craze’” within the emerging genre of caizi jiaren (才子佳人) or scholar-beauty romances, in which gender play was a frequent narrative trope.7 Robert van Gulik notes that within painting, “instead of the middle-aged bearded men of the Tang and Song periods, ardent lovers in Ming painting are more often depicted as young men without beards, moustaches or whiskers”.8

In a similar spirit Keith McMahon describes the change from rough-hewn heroes of the haohan (好汉) type to men of feminine beauty of the fengliu (风流) type in historical novels. And of calligraphy, an aesthetic form crucial for determining the spirit of an epoch, the Ming scholar Xie Zhaozi (謝肇淛) (1567-1624) wrote: “In our age, more scholars practise soft strokes than firm strokes.”9 In other words, within the world of the Ming literati the softness of yin (阴) triumphed over the hardness of yang (阳).The understanding of the triumph of yin over yang in the Ming period provides analytical complexities for the modern reader. It is important to note that yin and yang do not translate into gender division in the sense ascribed to masculine and feminine within English translations. Rather yin and yang describe polarities (or corresponding entities) operating both within the individual and society as a whole.

In such a cosmological model the ideal state is a harmonious balance between the two forces, and an imbalance in either direction is understood to lead to disharmony and chaos. Philosopher Feng Youlan (馮友蘭, 1985-1900) argued that it was the integration of yin and yang into a model of Confucian statecraft by the venerable Dong Zhongshu (董仲舒, 179-104 BCE), which led to yin and yang taking on a hierarchical dynamic of dominance and submission.10

Nonetheless, while Confucianism is understood to uphold a strict delineation of gender distinctions, it retains a space for the harmonious integration of opposites. In the Confucian ritual text Liji (礼记) or The Book of Rites the ideal ruler is described as the “father and mother of the people”, who combines the gentleness and compassion of yin with the strength and intellect of yang.

The ideal Emperor is thus a fundamentally androgynous figure. The Neo-Confucian Shao Yong (邵雍) similarly notes: “If yang predominates, he will be off balance towards strength, and if yin predominates, he will be off balance towards weakness.”11 Within Neo-Confucian philosophy the scholar-official was regarded as occupying a yin position in relation to the sovereign.

The cultivation of yin by the literati scholars within the Ming Dynasty was a means of addressing a deeper social imbalance. Namely, the tyrannical sovereignty of the imperial court. Zuyan Zhou notes that during the Ming period, when charges of political despotism were raised against the court, scholars maintained their independence by adopting a yin position, in other words, by foregoing official positions in favour of seclusion and eremitism.12 By adopting a marginal or yin position the scholar could maintain inner freedom from a dominant political authority.

One model that was held up by Ming literati was the Warring States poet and minister Qu Yuan (屈原, c.340-278 BCE), the first person in Chinese literary history to be banished and thus the archetypal exile. Qu Yuan is most famous for the poems collected in the Chuci (楚辞) or Songs of the South anthology written in the sao (骚) or lament style. His most famous work is the poem, Li Sao (离骚) or “Encountering Sorrow” in which the poet-protagonist travels on a celestial journey to find his ideal love but whose journey ends in self-annihilation. The poem has been interpreted as an allegorical reflection on Qu Yuan’s own political career, which ended in suicide after his advice to the King of Chu was ignored and the royal house was overrun and defeated.

Qu Yuan would be revered as a patriotic poet during the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE) and this continued into the modern period with Mao famously praising the self-sacrificing nationalist spirit of the ancient writer. But “Encountering Sorrow” is a work that pulses with androgynous voices.

The poet’s pursuit of his meiren (美人) or fair lady addresses the ruler (“the Fair One”) and the narrator’s identity as the submissive scholar slips ever deeper into the feminine register and the poet is transformed into a woman adorned in sweet smelling flowers who has been abandoned by her lover: “Dressed in selinea and shady angelica/And twined autumn orchids to make a garland”.

Many a heavy sigh I heaved in my despair,

Grieving that I was born in such an unlucky time.

I plucked soft lotus petals to wipe my welling tears

That fell down in rivers and wet my coat front.13

For contemporary scholar Song Geng (松耿) this adoption of the feminine voice is crucial to the androgynous position of the caizi or scholar whose exclusion from the court signals a deeper spiritual exile.14

Political androgyny was accompanied by practises of spiritual androgynisation. Taoism has long been understood as providing a counterpoint to Confucian orthodoxy in its celebration of the yin through the veneration of the Valley Spirit or gu shen (谷神). Indeed, Ming practitioners of eremitism often cited Zhuang Zi the Taoist master, who refused a position in the court to pursue a carefree life fishing on the riverbank.

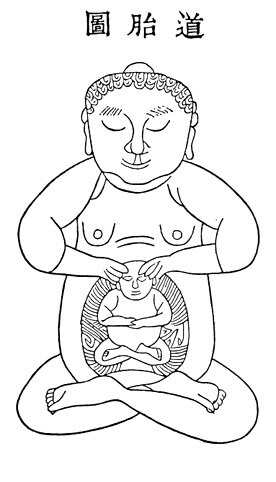

Spiritual androgynisation is a central element within Taoist sacred technics. Such practises are what Sloterdijk refers to as anthropotechnics. For Sloterdijk anthropotechnics are the practises of self-transfiguration that form the basis of all ascetic spiritual regimes.15 One such Taoist practice is that of Inner Alchemy, a meditation exercise which increases the life force or qi of the adherent. The aim is to promote the internal copulation of yin and yang in order to generate an indestructible diamond body.

One renowned form of Inner Alchemy involves the male practitioner envisaging a small embryonic child within their body known as an infant ying’er (婴儿) or “the immortal embryo”.16 The adept is thus transfigured through meditation into a male mother who will give birth to new celestial version of themselves. Yet the ultimate aim of the practice is to dissolve one’s physical gendered body by enfolding it within the greater formless androgyny of the Tao.

Such practices of inner alchemy are a syncretic combination of Taoist and tantric Buddhist anthropotechnics. In this regard we cannot investigate spiritual androgenesis without mentioning the Goddess Kuanyin, “the perceiver of sounds”, who is the Chinese iteration of Avalokiteśvara the bodhisattva of compassion.

Artistic depictions of Avalokiteśvara depict a being with thousand-arms or a thousand-heads with which he can listen to the suffering cries of all sentient beings. Avalokiteśvara appears in Chapter twenty-five of The Lotus Sutra, as a being who renounces personal enlightenment in favour of the enlightenment of all. The chapter goes on to describe the thirty-three manifestations of the bodhisattva, including its various feminine forms.

But as Chun-Fang Yü notes in her study of Kuanyin, none of the Indian avatars of Avalokiteśvara reflect this feminine manifestation. It is only when Buddhism came to China in the first century AD that Avalokiteśvara began to undergo a radical gender transition. Yü notes that by the early Song period (960-1279) Kuanyin had taken on a distinctly feminine identity and statues of the goddess were widespread in household shrines.17 “Everybody knows how to chant Amitābha, and every household worships Kuanyin”, goes the ancient proverb. Kuanyin offers us another powerful model of spiritual androgyny, as a perfected being who guides the worshipper as a model of both compassion and wholeness.

21st Century Androtechnics

After our journey through time, we return to the present day a little puzzled. What to make of the most recent return of the androgyne to China in these early decades of our century? It appears the fervour with which andro-idols are worshipped today is but the most recent manifestation of an ancient fascination.

Why then has this re-emergence of androtechnics been identified as a threatening motif by the Communist Party? CIA psyop or otherwise, it is difficult not to hear the drums of war in the calls for the return to masculine models in the Chinese cultural sphere. One could suggest that the suppression of the androgyne is the continuation of a wider project to maintain public order in a time of spiralling geo-political uncertainty.

Perhaps the androgyne haunts the Party as a spectre of the Imperial past, an emanation of a nightmare world of eunuchs and effeminate literati whose ambiguous gender constitution signalled the decline of the feudal regime. Cultural androgynisation in such an analysis is an augury of a civilisation in crisis.

The absolute devotion that pop idols inspire today could, alternatively, be understood as a form of spiritual identification, which lies in a curious relationship to the Party-State. In such a reading, androgyny retains its spiritual attraction as a way of attaining liberation from political concerns, albeit one in which spiritual exercises have been replaced by an androgyne economy of commodity obsessed xiao xian rou.

One thing is certain: The androgyne is an avatar of mimetic desire, which inspires acolytes to adopt a similarly ambiguous gender constitution and to eventually disappear altogether into a fragrant chamber filled with beautiful pop stars and their legions of faithful fans. It is no coincidence that the androgynous voice of the literati was one which was used to signal both devotion and distance from prevailing orthodoxies, one that while silent today may once again speak with a seductive tongue.

There is a perennial quality which marks the return of the androgyne in China today, bringing with it a host of latent fears, but fears which mask a deep longing. At the very least, the androgyne is a figure marked by its ambiguity—an ambiguity that invites an obsessive pursuit of aesthetic refinement and is currently snaking its way through the digital networks of the Sinosphere, entering the open hearts of its welcoming citizens.

Adelaide, 24th of June, 2022.

-

Mao Zedong, “A Study of Physical Education” (1917) Selected Works of Mao Zedong Volume VI (Secunderabad: Kranti Publications, 1990). ↩

-

Peter Sloterdijk, You Must Change Your Life: On Anthropotechnics (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2013), 27. ↩

-

Yan Fu, “Yuan qiang” (On the origin of strength), Yan Fu ji (Works of Yan Fu), (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1986), 5–15. ↩

-

Liang Qichao, “On the New Citizen”, Complete Works of Liang Qichao (Beijing: Beijin chubanshe, 1999), 655-735. ↩

-

Liang Qichao, “On the New Citizen”, 655-735. ↩

-

Carlos Rojas, Homesicknes: Culture, Contagion and National Transformation in Modern China (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015), 6. ↩

-

Zuyan Zhou, Androgyny in Late Ming and Early Qing Literature (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2003), 95. ↩

-

Robert van Gulik, Sexual Life in Ancient China: A Preliminary Survey of Chinese Sex and Society from ca. 1500 BC till 1644 AD (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1961), 294. ↩

-

Zhou, Androgyny, 16. ↩

-

Feng Youlan, A Short History of Chinese Philosophy (New York: Free Press, 1948), ↩

-

Shao Yong, “Huangji jingshi shu” in Theodore de Bary Sources of Chinese Tradition (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), 518. ↩

-

Zhou, Androgyny, 25. ↩

-

The Songs of the South: An Anthology of Ancient Chinese (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1959) ↩

-

Song Geng, The Fragile Scholar: Power and Masculinity in Chinese Culture (Hong Kong, Hong Kong University Press: 2004), 56. ↩

-

Sloterdijk, You Must Change Your Life, 109. ↩

-

Daniel Burton-Rose “Gendered Androgyny: Transcendent Ideals and Profane Realities in Buddhism, Classicism, and Daosim” Transgender China (London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 82. ↩

-

Chün-fang Yü, Kuan-Yin: The Chinese Transformation of Avalokiteśvara (New York: Columbia University Press, 2001), 6. ↩