Class warfare seems to be a positively outdated vocabulary. A blunt and dusty Marxist tool for social analysis, it evokes the deranged and reality-removed preachings of university unions. In the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis, when Occupy Wall Street announced the slogan “We are the 99%”, we caught a faded sepia glimmer of such mass vertical political polarisation. Not for long. We were ultimately dragged back into the inertia of identity-politics and sociological hyperfragmentation, which today seems more entrenched and irreversible than ever. Is class warfare that dead? Silent shrugging and embarrassed disinterest. The reason for the decline of the metaphor is also that few have adequately attempted to pay close attention to its transformations as a social phenomenon. An unlikely contender in contemporary political analysis is Brandon Cronenberg, son of the famous body horror daddy David. His work Possessor can be read as an ultimately contemporary piece of political sociology.

Plot

Possessor revolves around Tasya Vos, a trained assassin who uses brain-implant technology to enter the minds of unsuspecting victims and carry out remote-controlled and ultraviolent murder with their unconscious bodies. Vos’ employers are a discrete and professional organisation that organises hit jobs for rich clients. They hijack bodies which are close to designated targets to eliminate them publicly. Afterwards, the implanted assassin commits suicide with the body-shell. With the brain implant subsequently dissolving after five days, all that is left is a “clean” crime scene.

Yet the murder itself is only part of the service: The other part is that “the company” chooses its murderers in a way to provide a plausible, i.e. anthropologically appealing motive. As viewers we are witnessing this business model via the protagonist and assassin: Vos takes possession of the body of Colin Tate, the fiancé of Ava Parse, daughter and prospective heir of data mining magnate John Parse. Both John Parse and Ava Parse are the targets of the assassination, which is commissioned by Parse’s machinating stepson who wants both CEO and heir out of his way to take control of the enterprise. In return he is prepared to pay out “the company” as assassination service provider with a package of corporate shares and a large sum of money. Ultimately, however, the job does not go as planned. Vos murders John’s daughter but Colin Tate, the hijacked body, manages to disrupt the mission by recovering partial consciousness and damaging the implant, leaving the assassination of John Parse incomplete while both Tate and Vos struggle for control of Tate’s body.

Krieg

Possessor features multiple layers of class warfare: the first is intra-elite. Concretely, at the first regard, it is war between John Parse and his intriguing stepson. But what the latter does not know emerges in a conversation between Vos, the assassin, and her superior. The real target from the perspective of the company is their own client. After the successful hit, Vos’ superior announces that they will be able to control their client. We find here a reference to the universal political currency: blackmail. It is no coincidence that the name of the assassination service provider in Possessor is only “the company” mimicking the nickname of the CIA. We learn that parapolitical networks of highly technologised violence secretly run the show. They operate in a world of smooth and discrete logistics, employing accumulations of advanced technology towards an oblivious public. The company thus represents the corporate state and its blend of covert violence and amorality that slowly but securely cannibalises the productive economy.

We find here what James K. Galbraith called the Predator State: organised networks appropriating the institutional infrastructures of the state between military and private economy that were built as a public and somewhat democratic interface of the nation state in the 20th century. The tactics are high-tech paramilitary/-corporate logistics. A result of a monstrous sociological fusion: post-Cold War budget cuts lay off spooks who enter the corporate world and become reactivated post-911. Thirty years on, they silently control the corporate economy, while continuing to operate it via managers “held” by fat dossiers of kompromat. PPP intel centralisation runs the show while functional separation still exists as a Potemkin village for the public: The good state vs the bad private sector; The bad state vs. the good private sector. Beneath this is the spook-staffed privatised unistate run by a techno-Cheka employing maximum surgical violence and state-of-the-art spycraft. Just as the trader-strongman historically took control of the peasant, the spook-trader today sits on the back of the productive manager and occasionally spars with him. It is possible to detect here one layer of intra-social class warfare of the 0.01% which remains almost entirely hidden from the public eye. Perhaps more importantly, it remains hidden from a part of the elite itself: both Parse and his scheming stepson are completely unaware of the plot against them: society is striated by a permanent and ultra-violent intraelite struggle walled off by a labyrinth of asymmetric knowledges and impenetrable unconfirmed rumours.

Middle Clash

A second layer of class warfare in Possessor is that between the professional middle classes and the lower classes. Vos, the professional assassin, is slowly lured into management by her superior who announces her as a possible successor. Vos is the Professional Managerial Class incarnate: a member of that sociological bastard-class designated by the Ehrenreichs in the ’70s. The PMC is the Promethean aspect of the middle, it wants to escape and move upwards but remains locked in bondage between the capital that employs it and the humanist baggage that ties it to a contradictory (humanist but today often CSR “woke”) moralism, which it sometimes employs as a weapon.

Vos is illustrative of this bastard-managerial middle through her elite violent professionalism exacted via her petty bourgeois origins that she is still attached to affectively. The assassin maintains a double life, occasionally hanging out with her former husband and their child. The husband is an academic, thus harmless and obviously removed from the real of society. He doesn’t know Vos is a top dog butcher of high-profile targets. He represents Vos’ divided consciousness and the pull towards middle class values: a longing for moral normativity, which is the kind of contradiction that has historically produced the Snowdens and the Mannings of the world. This divided consciousness is portrayed early on in the movie when Vos, in a psychometric test by her employers, speaks of her persistent guilt over a butterfly she killed and catalogued as a child.

In the depths of contemporary deep internet lore, the butterfly is an almost universally recognised symbol of the CIA’s MK Ultra programme, and more specifically the so-called “Monarch programming”. Monarch programming is a trauma-based mind-control technique named after the Monarch butterfly aimed at cultivating total psychological control over “brainwashed” “Manchurian candidate” subjects. MK Ultra and Monarch programming epitomise the techno-scientific brutality of the 20th century. In this key scene, viewers are told that Vos cannot stomach the real of the 20th century, which inserts increasing amounts of unpalatable trauma-tech into the social. It is a transfer and extrapolation from individual to mass technique, outlined by Naomi Klein’s book The Shock Doctrine.

The humanist middle class citizen is precisely constrained by their persistent refusal to acknowledge the technological legacy of the 20th century and its unprecedented exploitation and near limitless1 control of both individuals and the masses reduced to a series of conditioned reflexes. Cronenberg directly addresses the behaviouralist psychology experimentation at the origin of and intertwined with trauma-based programming like MK Ultra. He alludes to the doctrine which conceives of the human as controllable machine2 by showing the footage of an electromagnetically stimulated bull incapable of attacking a matador. The mastery of such technology is elitism proper: a sphere which has separated itself entirely from herd morality considerations of fair play and dignity. Humans are conceptualised as a mass whose sole purpose is to be instrumentalised as productive, destructive, disruptive power. Vos’ initiation into the elite is complete when we see her upending her social and moral conflict by rejecting her petty bourgeois humanism. By killing her own son towards the end of the movie, she has fully resolved her divided consciousness by adopting what Sombart understood as the bourgeois mindset proper: cold calculation. The son embodies the original common project between the PMC and bourgeois humanist academia, which is eliminated.

The second protagonist is Colin Tate, introduced to the viewer as the future husband of Ava Parse, the second target of the assassination and daughter of CEO John Parse. Tate is chosen as a plausible assassin due to his social position. He is introduced by Vos’ superior in the company: “Father deceased, mother estranged, no siblings, deals cocaine for a few years, then falls in love and becomes engaged with one of his rich clients.” Tate is the typical marginal, a scumbag coke dealer figure of the subproletariat who attains accidental status through his petty crimes despite being an outsider in the social stratum in which he moves. Tate represents a manipulated and resentful class who are introduced into the PMC more or less accidentally (think quotas, celebrating the “Other”). More generally, the majority of this class is given free rein as a social chaos agent in what Sam Francis coined as a system of “anarcho-tyranny”.

Anarcho-tyranny stands for a purposefully introduced amount of chaos and lawlessness into society, through the highly selective non-implementation of law. The result is the introduction of a criminal subproletariat whose primary role is to harass the productive middle classes. The marginal subproletariat thus mirrors the parapolitical fraction of the elite operating amorally, extraterritorially, and illegally for the maximisation of self-interest.

In return, the harassed productive middle class is unique in its organisational skills and universal humanism, which makes it potentially revolutionary, dangerous and thus the main target of the predator state. Anarcho-tyranny fulfills the job of legitimising the security surveillance state and directing popular anger horizontally rather than vertically, i.e. towards these unconscious agents. Colin Tate is thus chosen to provide the body for the murder: his task as the lower-class unconscious agent is to eliminate the productive entrepreneur3 as the true elite competitor of the security state. After all, while the producer is comparatively immoral, he is sociologically closer to the middle classes on whose productive power he directly depends. In comparison “the company” is exclusive and only actually owns part of the economy. Financial capital allows for a spatial and operative separation of ownership and management. Its agents are functionally and spatially separated into control rooms and only intervene in social affairs, which are fundamentally abstracted and mediated interests—deus-ex-machina style.

In the course of Possessor, we see an interesting conflict in both (potentially) middle class characters. Vos’ conflict is that she is unable to commit suicide at the end of her hit jobs. We see her unable to fully dissociate herself from her petty bourgeois morality: to kill “herself” to become fully professional.4 On the other hand, Tate represents the manipulated social actor who becomes partially aware of his political determinations. He revolts against his remote programming through elite technology; through the injuries and abuse inflicted upon him, he partially escapes control and attains a potentially revolutionary awareness. In a symbolic scene, we see him adopt the grotesque and ill-fitting Vos mask, while flashes of her life enter his consciousness. For the manipulated proletariat, elite schemes often remain a unified mass of caricatural and grotesque conspiracies. They instinctively understand the war waged against them without fully comprehending the complicated network of techniques, mechanisms and mediations.

Both characters, standing for the larger population, are locked in the same body of fundamental interests: security, commoner morality etc., but remain essentially alien in their sensibilities and proclivities, which are exploited and pitted against each other.

Mediations

Another layer of Possessor concerns the exercise of social control by the “company”. While elite social conflict is triangulated via the lower classes, the company is not only selling murder but the fitting narrative. In marketing, this technique is called “Storytelling”. Storytelling is a technique popular with political consultants who insert a classical, relatable and “human” narrative to cover up machinations guided by cold calculation. While serious political analysis is always analysis of networks and interests, “storytelling” has shifted contemporary political analysis entirely towards the domain of the psychosexual: presidents and politicians are read according to “small hands” (Donald Trump), “stupidity” (George W. Bush5), “narcissism” (Nicolas Sarkozy, Emmanuel Macron), “blackness” (Barack Obama) or “womanhood” (Angela Merkel, Hillary Clinton). The public salivates over Lewinsky blowjobs but misses out on the spook story6.

In this way, contemporary democracy always operates at two speeds: one of hard Ge-stell technocracy (parapolitical violence, ruthless economic and political warfare, intelligence arms races); and one of the inert masses (slow pop-psychodrama, electoral politics, perpetual “incompetence” and the “ideological blindness” of the political and managerial classes). Democracy as “Storytelling”-style mass marketing is precisely the mechanism disconnecting the two. Politics needs to move at anthropo-speed towards which the masses inevitably drift due to their own psychological structuration, which refuses to understand the world as mediated and organised intelligence and interest.

Beyond anthropo-speed, the techno-speed of the managerial-come-predator class using cold calculation and icy technology increasingly spirals into the moral vacuum of sadistic, seceding, and warring self-interest. The historical sequence of Kincora – Dutroux – Iran-Contra – E-Team – PRISM – Pizzagate – Epstein is at the centre covered by the jolly layer cake of incompetence, indignation and “disinformation” policing. In short, you don’t want to go there. A world of ruin awaits you, traveller. Get your mind out of the gutter.

When hoomankind moves at anthropo-speed it self-serves and self-soothes. Enthusiasm for the shallow and superficial is rewarded emotionally, financially, socially. “If you didn’t believe in anthropo-speed, you wouldn’t be sitting where you’re sitting”, a warped CGI Noam Chomsky blabbers.

Schluss

The subtle and up-to-speed sociopolitical awareness is what makes Possessor perhaps ultimately contemporary. It captures the saturation of the social with a new class warfare, cryptic, rhizomatic, triangulated and transversal, pitting elites against each other and employing the middle and lower classes as weapons. In the process, the bodies of useful idiots, resentful marginals, PMCs and harmless middle-class academics are remote-controlled, seduced upwards or bumped off. We’re paralysed by its aesthetic of pervasive eeriness because the process is instinctively and hauntingly familiar. Ugly parallel narratives are unravelling and slowly seeping into public consciousness, an uncanny valley glitching between techno- and anthropo-speed. Reality transforms into a poison well of info fragments: toxic rumours infused by private and state disinformation, by the horror real of the 20th century rearing its head.

Choices are narrowing: Catch on to become infected collateral, trapped in spirals of impotent indignation and boomer perma-rage; get eliminated, freeze into depression, or let prestige lure you back into the theatre of parliaments and microcelebrities.

Can you handle the truth, Vos?

If you can, why not join the fun?

Epilogue

The weapons of the future are gradually developed and deployed, the eco-conscious Anti-Leviathan is slowly devouring the population, inviting and herding it in mass urban sterilisation camps, gooey matrices, preparing history’s most gentle, universalist and equitable genocide. The public sphere is irrevocably dissonant and fractured, but all airways are saturated with the grey noise of vicious rumours. Pervasiveness of “Sudden death” techno-speed casualties of crypto-rhizo networked class warfare: pharmaco-pollution between Fentanyl accident and Pfizer maximalism, “Climate Change”, quiet political assassinations merge as the expanding black hole T.A.Z. of democracy, a vortex of obscene and total paranoia. Stand tall or get sucked in. Stand tall and get sucked in. Quiet in the distance: the artillery arrivals of the Great Terraforming.

-

Near limitless = prone to historical accidents. ↩

-

See also the legacy of Cybernetics conceptually and functionally equating machine and animal as epitomised in the title of Wiener’s book “Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine” (emphasis added). ↩

-

Think here of figures like Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, etc. The epitomic manager who is always threatening to disrupt social relations with a mix of productive power and somewhat humanist consciousness. Thiel’s Palantir, for instance, strikes us as a privatised doubling of the NSA surveillance state with a potential to disrupt the Cold War behemoth. ↩

-

A theme of bourgeois initiation more exhaustively taken up in Infinity Pool. ↩

-

In fact, the high age of Storytelling is the post-911 propaganda campaign of political marketing which introduces a new frivolity into political analysis increasingly dominated by privatised mass media in the 2000s. For an example of increasingly neuroscientific intensive marketing of the age see George Lakoff’s The Political Mind. ↩

-

For the serious of the affair, see for example: larouchepub.com/other/2001/2833mega_spy.html ↩

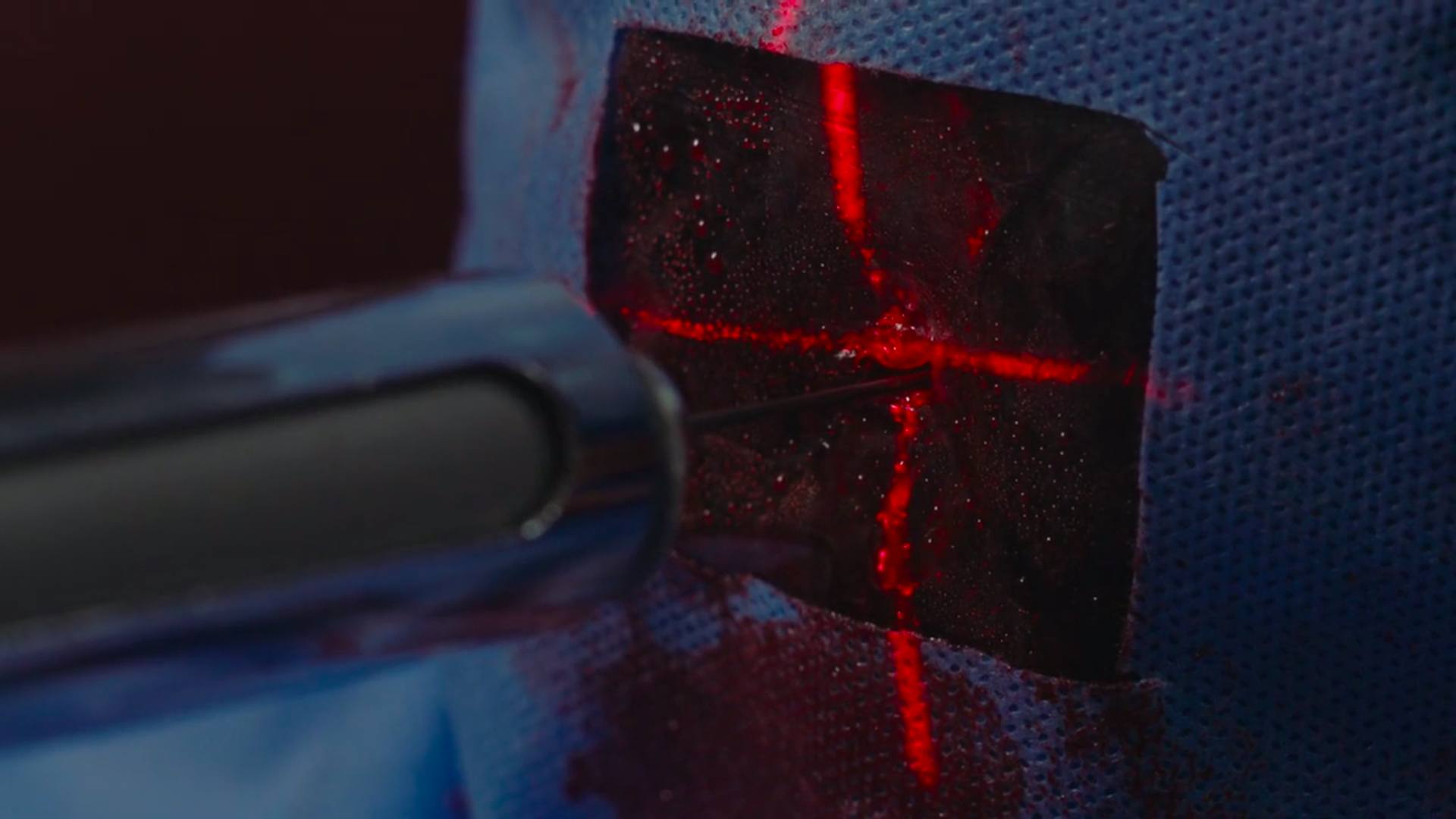

Cover image: Still from Possessor, directed by Brandon Cronenberg (Canada, 2020).