In 1894 the bubonic plague spread from its rodent reservoir via colonial trade routes, transmitting from Mainland China through Hong Kong and to the rest of the world. Over 20 million people died without account, buried by the heap, and the face of society was irrevocably altered. The extremist caricature of the West as a healthy, homogenised social body was upgraded and the human project entirely beholden to its inherited authority.

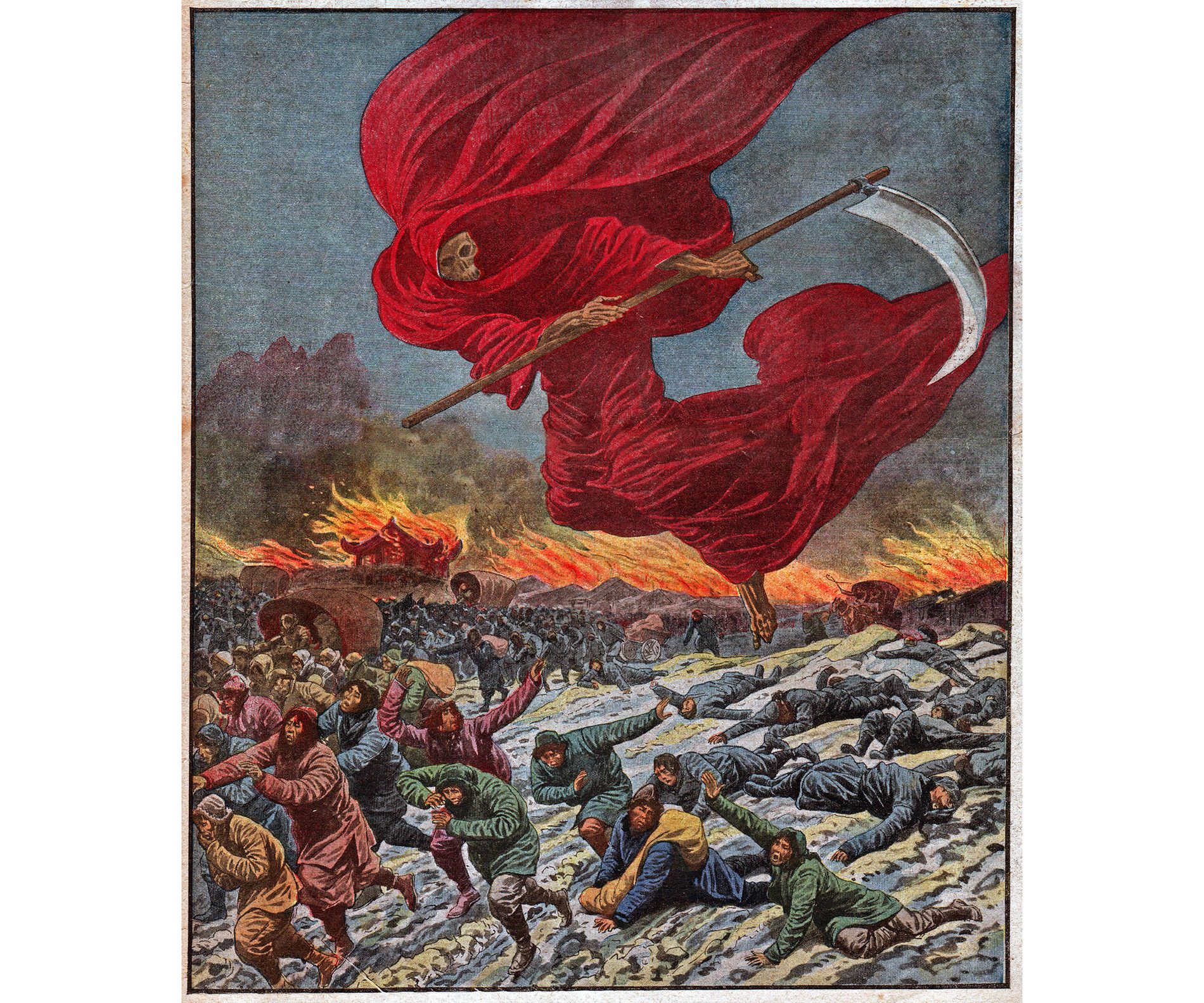

In 1911, the cover illustration of an edition of Le Petit Journal featured a horizon aflame and a red-cloaked grim reaper ravaging the landscape of Manchuria, scythe looming over the scrambling survivors. This time it was an outbreak of pneumonic plague that fed Western narratives of China as a carrier.

Time has not helped to exorcise the specter of Chinese contagion from contemporary western society and today’s globally integrated system is much less forgiving. The subsumption of life under capital extends to an ideal of freedom modelled on the freedom of the market. 2003’s SARS got off with a warning however, 2020’s COVID-19 has thus far been a mortal affront to worldwide axioms of negative liberty, exchange value and capital accumulation. As external restraints, fear and a duty of care enforce self-isolation, the language of freedom has become blatantly enmeshed with the economy, and every promise that we will endure tied inexorably to the resurgence of the market. Meanwhile, as we wait to “restart”, our sense of time begins to distort. We are confused about when we are.

On April Fool’s Day, during the SARS outbreak of 2003, the founding father of cantopop, Leslie Cheung 张国荣, finished a glass of orange juice and threw himself from the 24th floor of the Mandarin Oriental Hotel in Hong Kong Island’s central district. His suicide note, found in a pocket on his body, read:

Depression! Many thanks to all my friends. Many thanks to Professor Felice Lieh-Mak. This year has been so tough. I can’t stand it anymore. Many thanks to Mr. Tong. Many thanks to my family. Many thanks to Sister Fei. In my life I have done nothing bad. Why does it have to be like this?

The note read more like an acceptance speech than a letter of farewell, chilling in its thanks. “Depression!” seemed heartily confident in itself as reason enough. The trailing exclamation mark upbeat in its conviction that there really was no better way to put it. It(!)’s very understanding that it would be understood as causal, suggesting that deep discontent (providing you had an accurate estimate of things, like Cheung) is simply immanent to existence. Fair enough!

Despite health warnings, crowds of mourning fans congregated to pay homage to the superstar, people’s grief uniting them in clusters, spurring on the spread of SARS as they waited in the rain for Cheung’s hearse to pass. A moment of solidarity on the big screen veiling the microbiological feeding frenzy filling the spaces so politely maintained between them, contagion making the connections that they couldn’t.

It is again April Fool’s Day, the 17th anniversary of Cheung’s death and SARS’ sibling COVID-19 has infected more than 800,000 people worldwide. 2003-past and 2020future, twisting from succession to the brink of interactivity, a moment of noise that under prescriptive Western theory is commensurate with coincidence.

I call Mei in Beijing and I can hear Cheung’s 1984 hit Monica crackling in the background “Oh… as time goes by, oh I came to realise how precious you are” and on and on. For a month or so following Cheung’s suicide, his songs choked Hong Kong and Mainland China’s airwaves, an epidemic’s bittersweet pop backdrop breaking the threshold now to colour in my own pandemic experience. “Leslie Cheung’s Boyfriend Still Misses Him 16 Years After The Hongkong Superstar’s Death.” The SARS anthem plays on, continuing its upset of the historical order of things, of connections as causal conjectures along the taut line of consequence and missed moments. The friend on the other end of this spiralling timeline (phone line) has spent three months in self-isolation. Her term of restriction is drawing to an end and yet she has not made any plans to venture outside. The outside of the small apartment she shares with her mother is now a place beyond borders.

Mei has become an isolated and suspicious creature, constantly monitoring the news and others. Of course, there are risks if you are not vigilant but aren’t the dark and frightening days of COVID-19 in Beijing over? Or has the contagion actually mutated our very definition of freedom into a new, peculiar and narrow ideal?

“What is the Australian media saying about China?” she asks. It is easy to relate to such grim critical vigilance. This crisis, born from a bat, has born anew the bilateral ressentiment between East and West. “Thanks, thanks, thanks, Maria,” Cheung sounds sarcastic, “thanks Maria, waiguoren, external evil responsible for my nightmares.”

I don’t know what to say to her or to Cheung.

Time, plot and tragedy unite as their voices combine over the phone, background and foreground flattening into noise, redoubling universes, reloading presence into the present, into a new soundscape of mutuality. This convergence can speak Cantonese, Mandarin and English. Depression(!), Contagion(!) and Cheung(!) as time traveller, accelerating this moment of temporal torsion, layering infection and discontent. I say goodbye, zaijian (再见), or translated directly, “to see you again”.

“Things add up…” says my Chinese tutor over skype, she is talking about the West and seems to be inferring that our model of time follows basic arithmetic. “First SARS, now this.” Cheung isn’t playing in the background but there is again a distinct decentering of the clock, tock-tick. Tian Xue is already emerging from her hibernation somewhere three months into my future. What’s the date? It’s the 16th of April, over two million people have been infected by COVID-19, nearly 150,000 people have died and my indeterminate period of isolation has only just begun.

The progressive atomisation of society has led to the deconstruction of homogenous time. From my individual infosphere, I can’t see the evidence of things adding up. I reply in chengyu, “光阴似箭, guang yin si jian”. A classical chinese four-character form of idiomatic expression. I’ve interpreted this particular expression to mean “time flies” and say to her accordingly, “I hope that time flies”. Within a beat, I stand corrected, “光阴似箭, time flies like an arrow”. An arrow pierces and cannot fly without the activating intervention of a human apparatus. By such a definition, time exists as an extension of its manipulator. It is a beautiful thought, if we were the manipulator. I imagine Cheung holding a bow and arrow, the time traveler arrives again, caught in the distorting pull of another virus’ time machine. He begins firing arrows at its central warp core.

Classical Chinese thought, throughout the canonical texts, describes time as anything but a single, straight line and Tian Xue and I turn back to these texts now, at her three months from my day dot, uniting in a dynastical past. The very word for “time” in mandarin is confirmation of this aforementioned description of time—时间, shi jian.

Shi (时) infers time or fixed time. The character itself is the combination of radicals that paint a sun (⽇) and an inch (⼨) together, for the sake of poetic exacerbation and for

Cheung, it is the composite signifier of a sun inching across the sky.

The second character, jian (间) translates as the space between and among things. In a similarly poetic manner, it is the composite character of the radical for a door (门) and the radical for sun (⽇), a sun hovering within the frame of an open door.

Spoken together, shi (时) and jian (间) speak of time as both spatially and temporally unfixed, existing between, within and throughout numerous times. Its only portent to materiality is the cycling sun, an inference of human’s irrevocable accord with nature, read mortality. It can be attested that under a shijian model, time cannot be arrested. However, Tian Xue, for all of her study of the Yi Jing, (jing, 经) translates to “warp” by the way) cannot help but lament that under today’s inhuman systems, our arrows lay inert. Their apparatus for ignition stuck in a temporal loop, a “right now” that seems to translate as “the end”. I ask Tian Xue when she’ll be returning to see her acupuncturist, she too admits to me that she is too afraid to go outside.

~ Oh … as time goes by, oh I came to realise how precious you are ~

COVID-19 Mean Time, a new alien power of persecution? As our experience of time intensifies, we are compelled to continue to act purposefully and yet the common sentiment seems to be one of cynical resignation and despair. It cannot be denied that there must exist a relationship to common narratives of time however, need these narratives so profoundly guide us? It would be disadvantageous to succumb here and to postpone the capacity of our new time sensitivity to a date when the world restarts. Capitalism’s test drive of the virus crisis will only lead to a new vehicle in its garage of repertoires. Immediately, we have a humanitarian crisis that exists as more than just a political project. Despite external pressures, our “now” beholds a strange novelty, a temporal lurch that leaves a lot of space to explore and a lot of time travellers to meet.

Just as the streets of Hong Kong filled for Cheung and gave way to SARS, when COVID-19 gripped the district of Wuhan, medical professionals urged the people of Wuhan to stop screaming in solidarity from the windows of their tiny apartments. “WUHAN JIAYOU, WUHAN JIAYOU, WUHAN JIAYOU!”, specks of spit flecked with virus filled the winter air. It is now the year 2046 and BLOVID-45 has infected over 800,000 people worldwide. I can hear Dua Lipa’s 2018 hit, One Kiss, filtering through the cracked floorboards above me. If only we had known that one kiss really was all that it would take…