Audrey Schmidt: So, firstly, you had to review a sprawling exhibition that had no curatorial agenda or intentional overarching theme that no one else was able to attend. In how many words again?

Cameron Hurst: That’s a dire but accurate description. The VCA graduate show opened for two weeks in December with only “industry professionals” allowed to visit. This somewhat ironically included students from the University of Melbourne who were chosen to review the exhibition for Memo Review’s Mass Memo project. Each reviewer had 500 words to write on a few artists in a disciplinary section. There were about 100 artists in the Honours and Third Year sections of the Graduate Show, we were only allowed in for about an hour and a half and there were no wall texts or information available about the artists’ intentions.

What do you think the point of a review is? Especially in this pandemic context. Is it to provide a comprehensive document of what the show was like for people who couldn’t legally attend? To summarise themes? To pick “rising stars”? Maggie Nelson has described art writing as a “performative moment”. I like this way of thinking about reviewing, where it isn’t framed as a pious public service nor a totalising judgment of worth. Even though it was hard to review a huge, unthemed exhibition in a miniscule word count, it was also a fun constraint. For me, it became a concise exercise in style, perhaps at the sacrifice of considered content.

AS: I think artists—particularly young artists—always hope that reviews will perfectly distil the meaning of their works to “the public” (whether they were able to see it themselves or not), while retaining some of its mystique, showing that it could never be entirely “knowable”. Something they can whack on their CVs and build grant applications with. They don’t care if you achieve some sort of Maggie Nelson performative moment. At other times, they will try to resist interpretation all together and be furious at the thought of your having tried and inevitably failed. There are certain rules about interpretation, but many see it as a task of translation. And in one respect this is true, in that you are not rewriting the text, but you are altering it. But it would be a mistake to reduce art to its content and form—to try to “tell” “what it is”. To attempt a clean “translation” is a reductive exercise in making art more manageable. It is better suited to tasks like writing wall decals or the copy for an art fair catalogue (to marketing). For me, the point of an art review is to do cultural criticism through art—not to translate or rewrite the text, but to create a new one.

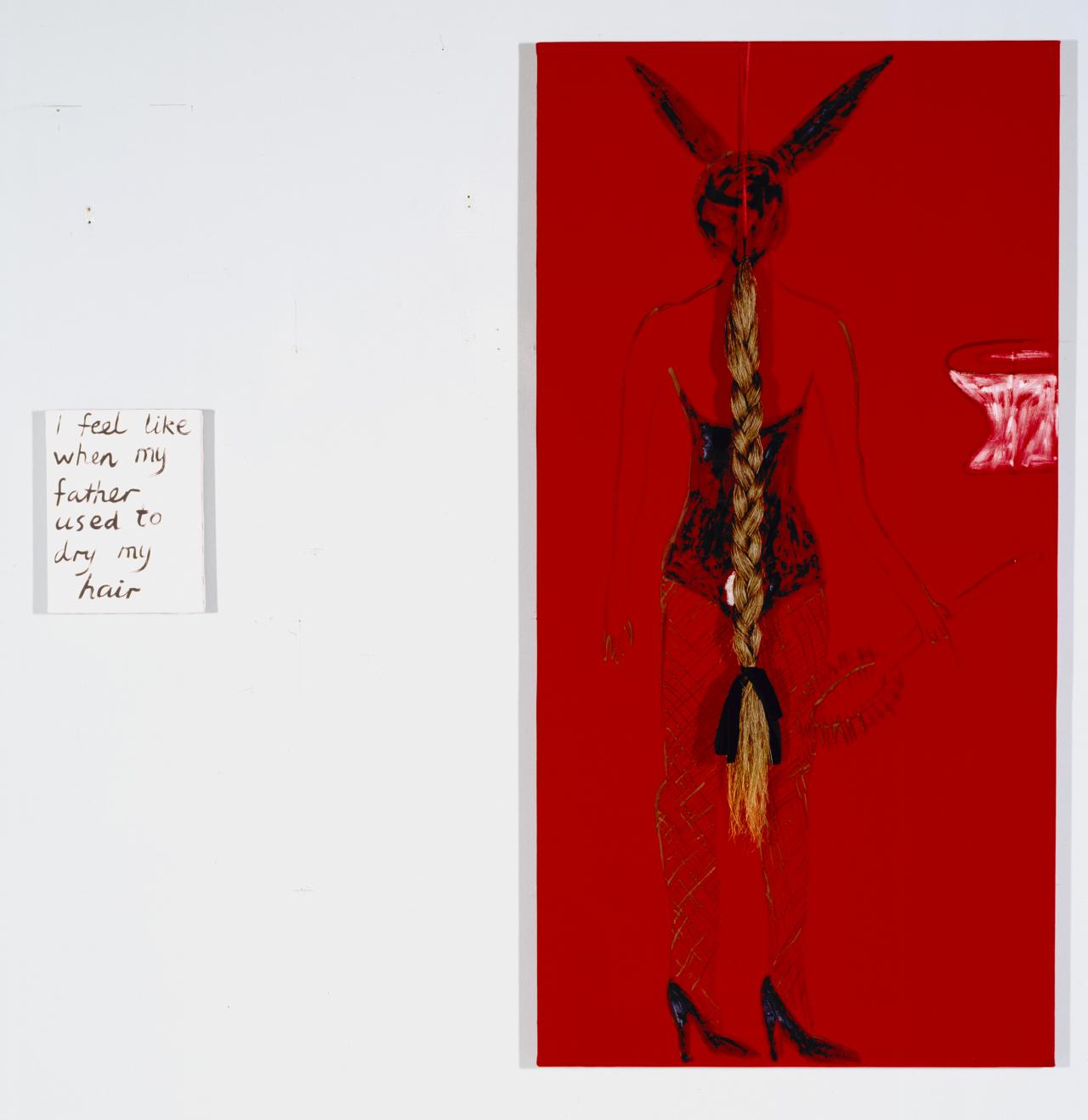

I think you did this as best you could in 500 words and maybe having no wall texts was a blessing. You identified what you saw as a “grotty girl” trend or movement among VCA grads and traced its potential lineage. My friend Kate kind of summed up the issues I had with “grotty girl”. It’s frustrating because it addresses the artist as the genre rather than the work—art as a symptom rather than an intentional gesture. From 2016–17 a group of us, including some of the artists you reference in your review, Hana Earles and Grace Anderson, ran an Instagram account called “Abject It Girls”. It was a muntdog69-esque joke account, but it was also a kind of cynical gesture in addressing how art (and social media accounts) by women are subject to more biographical scrutiny and critique than male and what it means to be an “It Girl” in a relatively small town. If we talk about grottiness, what separates the lineage of VCA alumni like Jenny Watson through to Hana, Grace, Evelyn Poggioli, Katherine Botten and new-gen Abella D’Adamo from other simultaneous lineages such as Ian McLean to Alex Vivian, Christopher LG Hill, Liam Osborne and Josey Kidd-Crowe (maybe new-gen Edward Dean after Lewis Fidock and Joshua Petherick)? Why add the “girl” qualifier at all? I also see themes of abject masculinity surface in different ways in Liam and Alex’s work. While all these artists have distinct practices, I feel like “crusty, grimy, oily” with a touch of saccharine sweet is a mainstay. They’re also often quite text heavy—“conceptualists of a materialist bent”?1

CH: OK. Firstly, a sheepish mea culpa. The obvious issue with “grotty girl” is that aside from addressing the artist as genre, it addresses the artist as gender, which is reductive and annoying. I actually originally wrote it as “grotty bitch”, which is a) funnier and b) dislocates gender from gauche biological essentialism into a more conceptual and campy aesthetic terrain (“bitch” is also far more “fucky” I think). However, it seemed too mean for a Memo grad show reviews of artists I had no personal relationship with. What do you think about that? Would “bitch” have absolved me?

AS: Bitch is still very gendered imo and at least “girl” is a nod to Preliminary Materials for a Theory of the Young-Girl by Tiqqun, which is less gendered but still cringe.

CH: That Tiqqun Young-Girl book exemplifies critical theory camp in its unfortunate failed seriousness. Admittedly it has some good lines, but my god, have these people ever heard of an editor? It’s a half-baked titillation for stunted hostages of the academy and the graphic design fucking sucks. Semio(ugh).

Those other male artists that you’ve listed clearly do orbit around a shared, intentional “grotty” visual language that is more linked by geography, time and social media than gender. Some of Steven Rhall’s artworks also come to mind. That being said, I think the grad show works (and the older artists who I originally situated them in relation to) do engage with explicitly “feminine” formal tropes and conceptual concerns. I never saw the Abject It Girls account, but the way you describe it speaks to this irresistible double bind. A form of curdled hyperfemininity is ironically deployed as a kind of meta-engagement with the tropes of “Women’s Painting” or whatever, but it is deployed nonetheless. The gesture is meant to trouble the need for the gesture, but inevitably reinscribes it and imbues it with new meanings and so on (a Galaxy Brain dynamic).

In the VCA show, it’s definitely true that other artists exhibited works that resonated with Abella D’Adamo, Grace Emerald Culley and Savana Szelski’s pieces (the three grotty girls I wrote about). Edward Dean, who you mention as a good example of a new-gen grotty non-girl, had crusty, oily work about signs and signifiers; Levi Franco had a bunch of aphoristic text pieces. I didn’t write about their work because it didn’t fit into my review word count, but even with hypothetical added space: Dean’s work isn’t particularly “girly” and Franco’s work isn’t really “grotty”.

I know you initially objected to my use of the term “fucky”. For the record, what is the correct application?

AS: Ok so obviously it’s a very silly word but for me “fucky” was always something very separate to Abject It Girls. It was in an exhibition catalogue for Spencer Lai that I tried to invent a fucky etymology and credit where credit’s due: Spencer is my mock destroyer linguist in crime. I describe it in terms as something with “the quality of being ‘off’—astray, adrift, spoiled, off-the-mark … art and artists that make the everyday alien, or just a little bit askew, creating environments imbued with an ambient uneasiness as opposed to explicit anxiety or instability.” A slapstick comedy comprised of the collision of people, objects and spaces. Actually, now that I think of it, “camp” is probably much closer to my definition of “fucky”. In Sontag’s terms camp is “failed seriousness”, “artifice as an ideal”, an anti-style that finds success in “certain passionate failures”.2 So maybe failure is where fucky, camp and abject collide—abject being failed Totality, femininity or seriousness and fucky being finding comedy in that failure (but without the ostentatious connotations of camp). But I’m interested to know how you see them as aligned. Chronologically? Socially? Comically?

CH: Some of those words you’ve used to describe “fucky”—“off”, “spoiled”—are typically abject in a Kristevan sense. Decaying flesh, congealed milk, these are archetypal examples of abjection. Your definition does seems more technicolour and clownish than would be considered classical in the abject palette. When I used “fucky” in the review, I mainly thought it was a funny, bitchy word, but I also considered it in relation to what I see as uncanny, campy craft traditions in Lai’s and others’ work.

Felt, graphite, coloured pencils, collage, embroidery, papier-mâché, denim and plastic (especially miniature plastic objects, especially “charms”) are all in the “fucky” material taxonomy, right? I’d maybe say Paul Yore fits the bill, but perhaps they’re too crochet camp. Lots of the work in Freedom is the gentle exploration of boundaries… I wear jeans, T-shirt, fragrance, a show organised by Lai at Discordia last year, is obvs fucky. That catalogue text explicitly invokes testing “the boundaries of the self”. In Powers of Horror, Kristeva writes that abjection occurs at the corporeal “crossroads of phobia, obsession and perversion” of the Self and the Other. It’s almost like “fucky” is a tempering of this raw, guttural process, which is rendered less violent by the addition of Polly Pocket knick-knacks and rainbow flag bags. Yet underneath fashionista stylings, an ambient unsettledness continues to seep through.

AS: I would say Yore’s work is more camp than fucky in its garish decorativeness and flamboyant queerness. Whereas in Zoe Jackson’s recent show at Bossy’s Gallery (run by Spencer and Madeleine Russo) for example, I think you see what you’ve identified as abject without being necessarily funny/fucky or camp. Could also add Amy Jane Parker to that category.

CH: Much of this work also eschews traditional fine art forms for a DIY spatial bent. You mentioned in an earlier conversation that this provisional materialism speaks to lineages of arte povera, where anti-bourgeois sentiments played out in structures made from “everyday” items. Germano Celant, who first theorised the movement, wrote referring to Jannis Kounellis’ work that arte povera spoke “the slang of natural, organic matter” that moved from the “‘said’ to the ‘unsaid.’”3 Germano’s distinction between the “said” and the “unsaid” articulates another idea I vaguely associated “fucky” with: a focus on subconscious, intuitive practices, as opposed to theory-based, PhDy work. In the interview text that accompanied the Recent Tendencies in Women’s Painting show at Guzzler, Hana Earles says that she “hates work that is research based”. To rephrase this in the parlance of our times, research is based. This is a junction where I see the abject/fucky overlay. It’s in contrast to artists like Tom Nicholson or Alex Martinis Roe, whose work is more concerned with practices like the interrogation of archives and processes of institutional historicisation. Important and interesting, but not juicy. In terms of arte povera “everyday” materials, the fucky/abject artists seem to be responding to the globalised supply chains that stock plastic-filled dollar stores. In addition to the enduring grotty efficacy of sticks, dirt and fabric scraps favoured by the Italians, the Melbourne avant-garde enlist Daiso detritus and duct tape. Kawaii arte povo?

AS: So they’re more research-cringe? I think any anti-intellectualism here is a joke. The fact is, these guys have all done research-based work as a condition of going through the university system. They would have written multiple exegeses where they qualify and contextualise their work with research. You can’t de-skill without first being “skilled” in some sense. So even if you are bucking against or rejecting this by employing a stream-of-consciousness automatism in your work, your conscious and subconsciousness has been shaped by your experiences—including those in higher education.

I think this is comparable to Trump’s appeal to an identitarian working class. A class that is not defined by class-consciousness per se but by the particular identity characteristics that are prescribed to it—a resentment not of the rich or of capital as the producer of class difference, but of professionals (Trump being a non-professional politician who is nonetheless rich/elite).

CH: Hmm, interesting. That point seems like a bit of a leap to me in terms of class (middle America to middle Melbourne? idk), but the rise of anti-professionalism rings true.

AS: Reminds me of the Jean-François Lyotard passage where he talks about political intellectuals, “privileged smooth-skinned types”, inclining towards the proletariat (who would hate them), but who dare not say that “one can enjoy swallowing the shit of capital”. Hana’s most recent show at Meow2, Victim of Late Capitalism approaches this idea, I think. In the audio work (accessible via the QR code on the room sheet that leads to a Patreon with a \$1 Victim Tier and a \$10,000 Patron of the Arts tier), the resentment is directed to a central (professional) authority figure that is a combination of writer, comedian, director, therapist, mother, policewoman (the Big Other) who was named Audrey in an earlier iteration on her old blog.4 “I want more every day. A bottomless pit”, “I don’t want to achieve anything. I don’t want to consume. I just want to make idealisations and ideologies and then focus on them and deconstruct them while they fall apart in front of my eyes. And I can indulge in the suffering until it feels less lonely”. So yes, this relates to materialism and global (over)consumption, to “Daiso detritus and duct tape”, but to play into my assigned role as analyst/therapist, it is not so much the hatred of capitalism as the jouissance of capitalism at play. Hana enjoys and indulges in the suffering, in victimhood. She’s an anti-professional professional masochist (AKA an artist).5

CH: Frankly, these psychosexual torture comms-by-proxy terrify me. I want to go back to the warm enclaves of the Big I institutions… to the NGV… to ACCA… to Uni… everyone is so kind and gentle there… kidding lol. Mummy Audrey makes me feel safe (I think).

AS: Lol Melbourne is not a safe space, sorry. But to continue traipsing along on my eggshell-laden path, from Punk Café to Suicidal Oil Piglet and Meow, I think we see a micro networked social order of artists whose oeuvres are generally a deskilled critique of authorship, the limits of “expression” and an unsettling aesthetic-force rooted in abjection. I also see a lot of “deferred” teen angst and perhaps this also links with abjection. When I wrote about Hana’s work back in 2017 for un magazine, I said that the combination of references to recognisable brands such as Subway and Sandoz, PornHub, Bratz dolls and so forth were about the identification processes that they encourage. While it could be argued that these elements constitute the artist’s autobiography, they’re not particularly personal signifiers. The significance of so-called postmodernist appropriation art that forgoes claims of originality by appropriating existing images and objects is that it exposes the fiction of the “unique individual” and that our senses of self are socially and historically determined by images, discourses and events.

In a lot of these artists’ work we see highly generalisable Western images (often commodities, advertisements and empty symbols like love hearts) of teenage or preteen girlhood. Ones that don’t refer just to specific autobiographies but to the mass media/networked technology that proliferated after Y2K. In a truly “unprecedented” way, coming of age came to mean that our primary identification processes were with television and computer/phone screens. It is a way of coming into being and gaining recognition, not solely through traditional institutions but also through our many dispersed, performative, social and mediatised personae. This is abject in the Kristevan sense—a process existing somewhere between the concept of the object and subject.

While identification was perhaps always a struggle between autonomy and deterministic outside forces, there is something in all these artist’s works that hints at the covert enjoyment or jouissance to be found in these processes (as with gossip). Enjoy swallowing the shit of capital, practice safe sex, go fuck yourself.

CH: I see “grot” as somewhat specific to the grimy culture of Melbourne. People here look like shit and so does their art. This links back arte povera, but I also see “grot” as a transnational artistic response to the aggressively naturalised minimalist aesthetics of the interfaces propagated by Silicon Valley acid bro libertarians. Wherever the Grid goes, a certain level of reactionary grot appears. We see this in decentralised art platforms like Solo Show. The formal and structural qualities of the platforms we engage with are constantly shaping our sensibilities, equally or more than their content—the potential for anonymity; the inbuilt assumption that anything can be copied, pasted and recontextualised; the primacy and gargantuan scope of image sharing; the potential for state censorship or surveillance depending on location and platform.

Having said that, the content is clearly important. Your invocation of “Western images of teen and preteen girlhood”, and the listing of brand names and TV show characters in the Earles un mag piece speak to this. They’re part of a shared lexicon inflected by a culture of hyperconsumption. This reminds me of something I observed on a flight recently. A tween girl in the seat next to me was playing a MyScene-esque game on her personal iPad which involved giving a makeover to a sexy animated female corpse (surely the penultimate Abject It Girl). My neighbour laboured over whether to pick orange or purple nail polish for her cadaver. All the best lip colours for grey skin tones were tragically paywalled. She peeked up at her Dad to suss whether he would give over the credit card, then decided the better of it. It was a perfect iteration of how feminine subjectivities are shaped by online life; a solitary fantasy of gendered identity construction as a process of accrual (I wear jeans, Tshirt, fragrance), mediated by access to Daddy capital.

Abella D’Adamo’s work, replete with branded, adolescent eroticism, represents what this preteen iPad gamer can graduate to in a few years’ time. teen amateur makeout stick and poke, D’Adamo’s video work, zooms on two teens passionately humping in an abandoned field. Crucially, the girl wears Cheap Monday jeans. The best art about the internet is never a literal, indexical re-staging of the digital in the art space (death to memes in galleries) but work that physically captures some intangible sensibility of what it means to be online. In D’Adamo’s work you can feel the deluge of images she’s scrolled through, even though the end result is a single figure or a one-channel video. This digital inflection isn’t present in the work of other, older artists we’ve mentioned like Jenny Watson, but I think it clearly starts to come through with artists like Chris Hill.

AS: Good point. You can make art that references the not-so-ambient omnipresence of the internet without making “net art”. Actually, in the Fucky catalogue essay I wrote: “A hypercomplex web of influence that sees the re-staging of the detritus of ‘life’—vignettes of fucky assemblages and modes of display that produce a distinctly uncomfortable humour… An industrial irrigation system of influence that mirrors the constant influx and accessibility of all things in the Information Age.” So that’s kinda exactly what I was getting at.

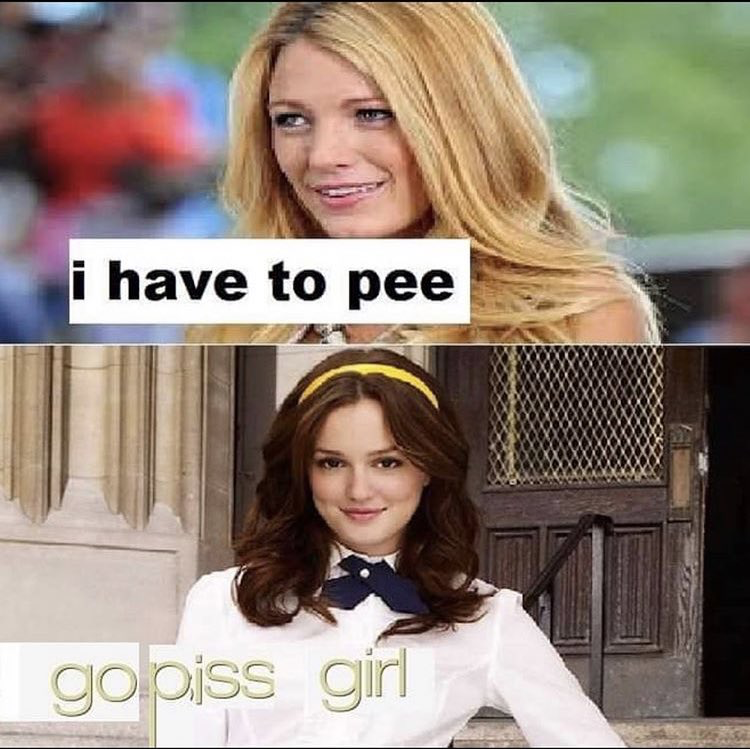

Ok, let’s move on to the next item on the Minority Sorority agenda—gossip. I don’t know how Giles mistook Gilmore Girls for Gossip Girl in his review of the grad show, as they’re wildly different shows with pretty different audiences, but I think it perfectly encapsulates a tendency to conflate aesthetics and trends that are seen as feminine under one “trashy” banner. Gossip is seen as trivial or intellectually unproductive, something that is generally understood as an intimate or personal way of talking between women. Of course, he sees that as horny because it’s something he does not have access to—a definition from the outside. Despite being the biggest gossip in Melbourne, he never really has the juice. Anyway, it’s just like abject: women are considered more abject/grotty because there’s a societal expectation to have more dignity or composure and when men gossip, it’s not trivial, it’s intel—because their words have more weight. After all, Dan Humphrey only used the Gossip Girl blog to write himself into his love interest’s life and to bolster his career as Dan Humphrey—author of the poem Sluts, which was featured in The New Yorker.

CH: I’ve never seen Gilmore Girls but I did recently rewatch Gossip Girl. It is incredibly glamorous, dastardly and gleefully obscene in its aspirational elitism. I feel like you’re more of a Blair than a Serena? I identify with (early seasons) Little Jenny “J” Humphrey, a bright-eyed, hopeful newcomer to the Met steps… How deep into a “micronetworked social order” do you have to be in order to qualify to make comment on the artwork that emerges from it, anyway? Asking for a friend. I moved here from Perth a few years ago, so I don’t know the interpersonal dynamics of local art history pre-2017. They don’t teach Suicidal Oil Piglet in the Art History classes at UniMelb (yet).

AS: I don’t think you need to be “inside” the network to comment on it, but I do think you need to understand it contextually. In Howard Becker’s terms, the “ArtWorld” is a network of cooperative links between institutions, artistic production, reputation building, circulation, distribution, consumption, interpretation and evaluation.6 Which is why much politically engaged art concerns the art world itself—a hermeticism that speaks primarily to those within that world. While these cooperative links were seemingly expanded post Y2K, there’s something that remains particular. It hasn’t been a process of acculturation so much as syncretism.

As a participatory culture, these artists transform the more “global” experience of media consumption into the production of new texts and communities that remain culturally specific, while absorbing the signifiers of more global cultures that they affirm while they protest. I think you can see a really clear comment on this in Zac Segbedzi’s eternally [self-referential (and gossipy!) work like, *The provincial subjects strike their self conscious poses in hopes of being validated / Early Career Group Show, which was shown outside of the Melbourne-context in 2019 at Jenny’s in Los Angeles and features the likeness of Hana, Calum Lockey, Natasha Havir-Smith, Grace Anderson, Liam Osborne and Kat Botten. (RIP to the aptly titled melbournefineartgossipblog).

I don’t think Zac’s audiences in Los Angeles needed to get the interpersonal drama in order to understand the premise of subcultural identity, competitive provincialism and international/institutional validation. But they’d definitely miss some of the nuances, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing. I think of Terre Thaemlitz’ “Secrecy Wave Manifesto” where she argues that in our quest for visibility, we have lost the cultural value of secrets, which preserve subculture within the social dynamics of minor communities. Thaemlitz meant this specifically in relation to queer spaces and curbing the indiscriminate distribution of her work online, but perhaps we could think of it in terms of the work’s actual content when it comes to Zac’s show. Even gossips have secrets. Perhaps they’re the most secretive of all.

CH: Sure. I don’t think an art writer or reader needs (or wants) to know the various interpersonal dramas of a scene to engage with the work coming out of it, but understanding “subcultural identity, competitive provincialism and international/institutional validation” as general features of (anti)professional artistic life is pretty important.

Now, back to the gossipy section of the docket. Interest in “gossip” in practice doesn’t seem to be particularly gendered. Doomer Dad Giles’ Mass Memo review was fixated on gossipy interactions as a result of quarantime repression. And in the Guzzler interviews, David Homewood said that Evie Poggioli’s work “makes [him] think of teen girl drama (gossip, emotions, crushes, confessions, drawings in diaries)”. What’s up with this recurrence of “gossip” in the lexicon of decidedly post-adolescent art bros? The word retains an ambivalently feminised libidinal frisson. They want in? But it also has somewhat pejorative connotations. As you mentioned, gossip often isn’t seen as erudite or intellectually serious. They want out? Maybe I’m projecting. The Google ngram shows that “gossip” had a moment in the bitchy mid-19th century, then a dip, then a meteoric rise in use from the year 2000. Is it time to flatten the curve? Gossip is always enticing, though, and I’m theoretically pro the destabilisation of gendered epistemological hierarchies… so I guess what I’m saying is that, despite it all, I’m interested in “the juice”. Would you say that you have it, Audrey?

AS: Well, as Dave writes of me in those interviews, “her opinion counts, but is she always a reliable source?” This idea of having to be a “reliable source” is sort of the antithesis of gossip, no? I should have something serious, researched, reliable to say but the inference is that I don’t—all I have to offer is “opinion” and the triviality of unfounded gossip. On the other hand, a source of what? Perhaps I’m not even a reliable source of gossip—propagating trivialities that are so dubious no one should believe or repeat them. So I do and do not have the juice. I am the fantasy of juice lol. Therapist, mother, policewoman, gossip.

As to whether I am a Blair or a Serena, I think we’re all encouraged to relate to Jenny because Gossip Girl came out after what I call the self-reflexive teen comedy golden era (imo between 1999-2004). Films like Never Been Kissed and 10 Things I Hate About You in 1999 through to the grand finale of Mean Girls in 2004 were all laced with a kind of Scary Movie self-parody excess, which was only possible because of the over saturation of coming-of-age films in the 80s. Riffing off Sweet Valley High, the popular girls all look the same and so the quirked up snowflake nerds end up being the protagonists (is this where it all started??). They fostered nerd individualism more than Breakfast Club/Fast Times ever could. Like Jenny Humphrey, perhaps I aspire to be a bit of a Blair but I’m not rich or popular enough. Although if I have to be an authority figure, I would much prefer to be Chuck Bass—the horny go-to guy when something naughty needs to be said or done. On a good day, on pay day, I’m Chuck Bass.

“I can tell you from experience, everyone loves a villain.” — Chuck Bass.

CH: I’d put in a Jenny quote but they’re all incredibly boring. Upon reflection, she really only functions as a cautionary Icarus in fishnets. I’ve changed my mind. I want the other Humphrey. I’d trade it all for a New Yorker byline.

AS: Maybe you can write my scandalous biography once I’ve coughed up my best and most salacious content. As Chuck Bass says, “people like me don’t write books, they’re written about”. But in all seriousness, we can probably agree we are none of these characters, right? They remain obscenely aspirational. In much the same way there is something that sets our grotty artists aside from artists like New York-based Bunny Rogers, who clearly investigates the cultural archetype of the Young Girl too. Instead of soiled mattresses and bed sheets, in Rogers’ work we see slick avatars and objects that don’t really comply with your grotty girl definition. They’re too clean/polished/inhuman.

In 2013 there was an exhibition called Lonely Girl curated by Asher Penn at New York’s Martos Gallery that grouped seven female artists under thirty (including Bunny) not unlike Guzzler’s Recent Tendencies. Except where Guzzler seemed to (however ironically) group women together by virtue of their grot-girl aesthetic and gender identity, the Lonely Girl press release read: “The artists in this show represent an unprecedented moment in cultural history—where the artists themselves can be equally or sometimes more visible than their artworks themselves.” Here I think we get to the crux of the issue, not only in the sense that it is about women being subject to more scrutiny than men based on their public persona/appearance, but we also see a grimy distinction. The Bunny Rogers, Amalia Ulman ilk are essentially Big Apple socialites—micro-celebrities—and here in lil’ ol’ Melbourne, we are certainly not as seen nor as desirable. Guzzler is, after all, a dirt-floor garage in the outer-suburbs run by two social pariahs pushing 40. Isn’t that more abject in and of itself? Being abject is basically to fail as a subject/object of desire and consumption. This is something that Bunny and Amalia essentially succeed in enacting, but it’s a positionality that seems much less accessible to “our” Abject It Girls.

In being non-celebrities, are Australian artists the last remaining artists that can lay claim to a “bohemian”, outsider status? Maybe this is why we see the grot and grime bubble to the surface most pungently here.

CH: Perth is often touted as the most isolated city in the world, so perhaps I have a provincial relativism, but I don’t think I wholly agree with this characterisation of Melbourne specifically as an outsider city. But nor do I think it’s entirely true of the whole of Australia. Even though Australia is geographically distant from the supposed cultural epicentres of the US and Europe, the flow of the internet along the lines of capital and colonialism mean that we are arguably all tuned in to the same platforms and content. And Australians also have access to a certain level of basic material stability (albeit steadily eroding), which has facilitated global mobility, visibility and “bohemianism” throughout the 20th century to now. Melbourne seems like a site of second or third tier cosmopolitanism (although now more distant from the action than ever as we’re locked down on the continent). To me, places like Namibia or like, Uzbekistan seem truly provincial, both on the planes of online life and in terms of potential mobility to the “important” locations. But in relation to art world hierarchies, is that just completely naive? Does only New York matter, still?

In terms of the blurring of social media personae and exhibited work: I think it’s both interesting and not. Scrolling through, for example, Adamo’s Instagram was a cool archival insight into her practice. But I appreciated her work without it and a lot of artists I like seem to be pretty bad at performing a successful online persona. Artists that achieve some degree of transnational visibility online through relentlessly performing their image also seem to attract pathological derision (e.g., Minna Gilligan). Is this a digital micro-celeb extension of Australian cultural cringe? Maybe.

AS: It’s much more socially acceptable to toot your own horn in America than it is in Australia. Besides that little proviso, we regrettably share a lot of cultural values with America that stem from colonialism and the Dream of upward mobility. But we also lack US and euro visibility—Melbourne in particular lacks presence in international biennales and the global art scene more generally (outside of Melbourne’s home away from home, Sandy Brown. We might not be Namibia or Uzbekistan but we are not the “Leaders of the Free World” either. And where is China in this equation? Online life is defined in China by an entirely different set of code, interfaces and content but they are nonetheless online. While they have the most comprehensive and sophisticated tech, internet censorship policies and algorithms in the world at the present, the West are trying their best to catch up. “Access” here starts to become a more slippery term.

In terms of an internet connection, at 68th on the Speedtest Global Index, even Australia’s internet speed is well below the global average—slower than India, Kazakhstan or Latvia. Even so, the internet isn’t democratising for those that do have “access” (however slow). It’s a very techno-utopian view that the internet obliterates old hierarchies with its decentralised structure and free information sharing etc. Algorithms and censorship aside, as I said in my pandemic art review, artists have been able to upload and promote their work since the inception of the internet, but to reach broader audiences they must be associated with a brand (e.g., influencer status) or an institution that can verify their legitimacy and ideally remunerate them. So, like, I still think there is an inside and an outside, even if it’s a bit of a moebius strip. That being said, I think New York is dead because artists without trust funds or sugar daddies can’t afford to live there anymore. And yes, bohemianism proper requires a certain level of financial stability for more than the elite few. This was the basis of the so-called counterculture of the 1960s—where in large parts of the Western world, scarcity was reduced so that the newly emergent bohemian class didn’t have to work as much and could determine their own time. So maybe Australians have the perfect conditions for countercultural bohemianism? Or, without the political optimism of the 60s, are the floating signifiers of counterculturalism and Daiso detritus all that remains in what feels more like “late anti-capitalism” than the hotly contested descriptor “late capitalism”?

CH: Cities with strong Wi-Fi connections and English as the primary language aren’t that outsider in a “planetary scale Stack”. Imo and to conclude, techno-utopianism should have a comeback and we need to talk about China. The early “cyber” theorists got a lot of stuff wrong, but they were also inspirationally committed to tech literacy/DIY and devoted to eroding the primacy of the West (albeit often in feverish neo-Orientalist prose stylings—Sadie Plant, I love you, but yikes). The internet will never obliterate old hierarchies, but old hierarchies are in the process of being obliterated and the internet will follow. The US is in immolating decline. Within Asia and its diaspora, there’s a rich intra-exchange of art histories that are shaping globalised aesthetics and discourses and will continue to do so without giving a shit about what micro-celebs in New York think. In a recent salon discussion, Caitlin Mason schooled you and I in the history of Abject It Girls in the Chinese art world. In our important roles as professional gossip girls, we can’t get stuck repeating “the West and the Rest” paradigm (to quote the legendary theorist Stuart Hall), nor uncritically deferring to the demons at Alphabet and Facebook.

Maybe the conditions for a new Australian countercultural bohemianism exist, but it will be different to the 20th century post-war insides and outsides. Post-covid is incoming baby, get ready. It’s going to be a whole new game (and yet, exactly the same old one). Buy your crypto. Get on Discord. Disavow English language hegemony. Whether you subscribe to late-stage or post- or neoliberal or anti–capitalist realism… swallow some shit. Enjoy it.

How did we get here from grotty girls? Nah, it’s all connected. Shit’s abject.

-

Ian McLean, “Artistic encounter: Jon Cattapan and Ian McLean,” ART150, 2017. Accessed January 9, 2021, from https://art150.unimelb.edu.au/articles/artistic-encounter-jon-cattapan-and-ian-mclean. ↩

-

Susan Sontag, “Notes on ‘Camp’” in Against Interpretation and Other Essays, (London: Penguin Books, 2009), 287, 288, 291. ↩

-

Germano Celant, “Jannis Kounellis,” Domus, no. 515, 1972, 55. ↩

-

She writes in the original: “my lawyer reading my tarot cards in the courtroom: writer, comedian, director, policewoman … my therapist decides to become my lawyer … I get a therapist (played by Audrey and/or memo review) she adopts me as a 26 yo, she raises me to be her own.” ↩

-

“Jouissance alone enables the abject to exist as such. One does not know it, one does not desire it, one simply enjoys.” — Julia Kristeva and John Lechte, “Approaching Abjection,” Oxford Literary Review 5, no. 1/2 (January 1, 1982): 131. ↩

-

Howard Becker, Art Worlds (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982), 34. ↩

Cover image: Grace Anderson, [detail] leave a message, 2020 in What is this hip-cock? We need more femcees… Women gave birth to all rappers anyway at Guzzler, Melbourne. Glo mesh in dirt floor. Courtesy of the artist.