25-03-23

Audrey: Do you remember how this all started?

Arthur: It was my suggestion as far as I remember. But I first thought of the idea by going to house shows with you and thought, “you can just do this in the suburbs?” I stopped painting as much as I used to because I didn’t have any place to show my work. Because we had to sell June’s1 house, the thought of everything that would end up in the tip made me think about all the art in the world that is not shown and just becomes landfill.

Audrey: Ok well I remember it a little differently. Remember when I asked you, long before Gemma died, about a few of your paintings and you said “what’s the point, they’d all be so mouldy and rotten by now”?

Arthur: Yeah I do remember. Resurrect them for what? To take them home to Melbourne to sit in my car park?

Audrey: Well you had this sense of entitlement, like I should put on a show of your work because I write about art. This is the only way I could think of doing it that made sense to me.

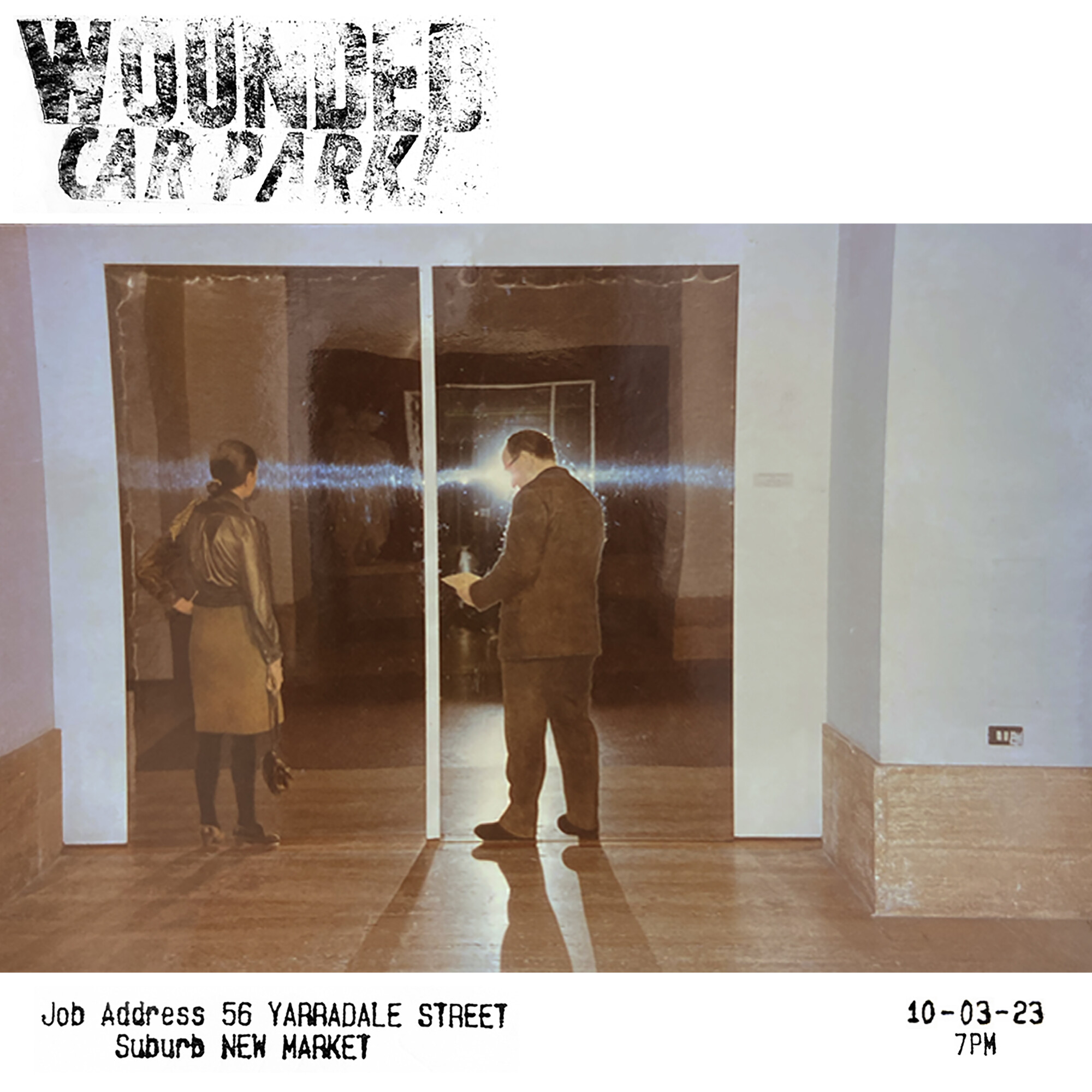

10-03-23

Audrey: Did you know just how many paintings we would find at the house?

Arthur: I knew when we left Brisbane that we had stored some paintings with June. I expected there to be a lot because Michael was prolific as an artist. He lived for art. He was monkish in his approach and devoted himself to painting.

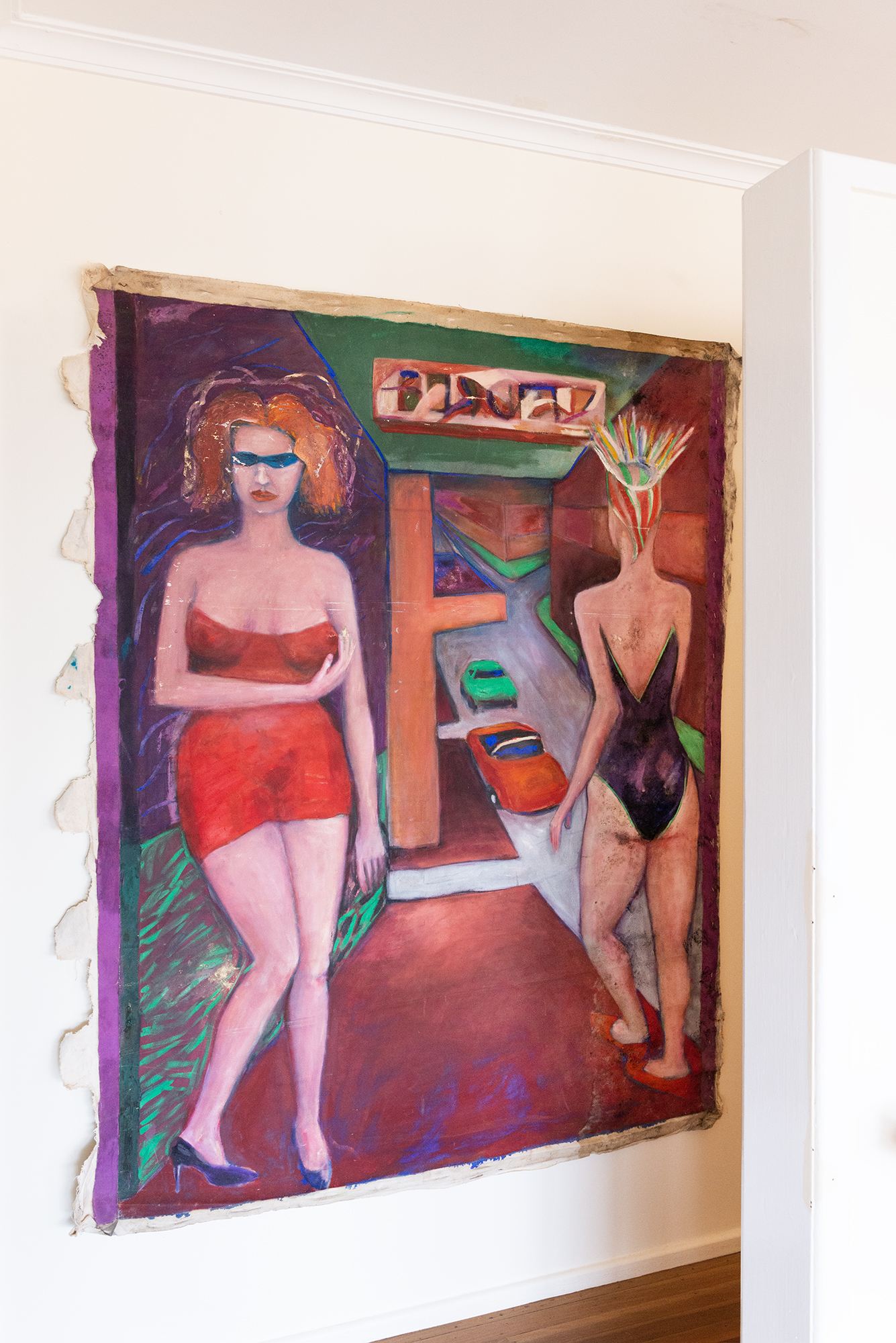

Audrey: You and Michael went to art school here in Brisbane and you both produced a lot of work. I know you got hung in some major art prize exhibitions, but neither of you actually ever had a show right?

Arthur: Right. I’m in the strange situation of being hung in the Art Gallery of New South Wales every year from ‘84-‘87 (Archibald and Sulman) and once in the Queensland Art Gallery in ‘77, but was never actually picked up by a gallery. The painted ladies in this show was hung in the ‘84 Sulman Prize. I also did a portrait of Ray Hughes for the Archibald (1985, location unknown), which surprisingly got hung. It was Ray Hughes with his stable, wheeling and dealing with his hunting trophies. He didn’t like my satirical take.

Audrey: How did you come to meet him?

Arthur: In my final year of art college I took up most of the walls with my paintings. He came searching for talent and asked me to come and see him so I went with my mate Mark Warne.

Audrey: What did he say?

Arthur: He said we were country boys.

25-03-23

Audrey: You’ve been to Guzzler (RIP) a few times with me, did you ever think about doing something like that at the time?

Arthur: No, I was not connected to the arts community at all. I felt false sometimes even going to openings. I’ve just never been community-oriented or a good networker, I was always quite reclusive.

Audrey: Were other people? What was going on?

Arthur: There were group shows. Artists would get together to try and get a group show somewhere. Gallery directors would stick with their cohort and I thought that was the only way to get a show.

10-03-23

Audrey: What were your career expectations leaving art school in ‘77?

Arthur: I dreamt, like Michael dreamt, that one day we would be discovered. That the good stuff rises to the top. But by the time the ’90s came around, I was stacking up work under the house and I thought, what’s the point of producing art that doesn’t get seen?

Audrey: How did one go about getting a show or representation back then?

Arthur: They didn’t teach us anything about that in art school. I don’t enjoy going to openings, never have, gives me some sort of social anxiety. Neither I or Michael did anything really to assist our careers.

Audrey: And you wanted to make it a career?

Arthur: Yes but I also suffered from imposter syndrome.

Audrey: You moved to Sydney in ‘83, Michael had already been there for two years. Then he left for London in ‘85-ish, where he lived for the rest of his life working in the service industry and hospo. You also lived in London for a few years in the late ’70s. What made you want to leave Brisbane after school?

Arthur: To see what was over the horizon. Brisbane is on the periphery, London is at the centre (or one of the centres). I did a post-grad at The Byam Shaw School of Art and painted mainly large abstracts. I left early and went to Morocco for three months. Even then I was worried about my commitment to art. Michael liked London because it was the centre and he would go to all the shows, all the openings, he knew much more about art history than me actually. He was a fan.

25-03-23

Audrey: In Sydney, you and mum started up the fashion label in the shop front of the place you rented off Oxford Street in Paddington. Wasn’t that a bit DIY?

Arthur: We did put on displays of fashion and art I suppose. But at the time, we thought it was definitely more about fashion than art because we thought that this could be a showplace. It was where we showcased our stuff to buyers.

Audrey: So fashion and art were completely separate for you at that time?

Arthur: Yea, in some ways fashion is a dirty word to an artist in that it could mean you are following a trend, a fashion, and not being authentic, original or sincere. Fashion is seasonal.

Audrey: It seems to me that it’s also because you saw the items as commodities more than your paintings.

Arthur: Yea definitely.

Audrey: Why is that?

Arthur: Because clothes are also a utility. And we were showing our ranges to stores, hoping to sell and make a profit.

Audrey: Ok but how is that different from taking your paintings around to someone like Ray Hughes?

Arthur: For a start, it’s not my work. Christine was the designer. Some of her earlier designs were more out there, avant-garde. I think she always struggled with that, trying to do something that was going to sell but that would still be her expression as a fashion designer.

10-03-23

Audrey: What was the fashion business like in Sydney in the ’80s?

Arthur: This is what Crown St congo (1983, location unknown) was about. A boy from Brisbane being in the big smoke of Sydney, enjoying the cafe culture, street culture, heroin culture. We started up a label ironically called Christine Door, but people didn’t seem to get the joke. So then we started the Christine Schmidt label and it had some success with editorial in Stiletto, Follow Me and even Vogue and Harpers. We both worked our asses off. But with late-payers, interest rates, we had to close the doors in ‘88. A few years after you were born in ‘89, we moved back to Brisbane.

25-03-23

Audrey: Did you ever do a runway show?

Arthur: Yea we did. Usually we’d show in the studio, in the shopfront. We’d have a model in and show our range. We did join a show with other designers and bands in the mid ’80s. It was a fashion/music show. Hunters and Collectors played, but I can’t remember anything else about it.

Audrey: Do you think paintings have some sort of utility?

Arthur: They’re more interpretive.

Audrey: Well, what did you think of the way I installed mum’s work?

Arthur: Yea I like that. Because it led you down the corridor, away from the two-dimensional work into a three-dimensional space, which was nostalgic for me. I also saw the images of the lost dream in the crumpled Christine Schmidt bags.

Audrey: More nostalgic than the paintings?

Arthur: Yea, the things were still separate. We saw fashion as a commercial venture. As much as I would have loved to sell paintings, I never saw it as having as much potential in terms of income as fashion.

Audrey: I know mum is an advocate for the firm differentiation of fashion and art.

Arthur: She is.

Audrey: I found an image of the Paddington place and you had paintings up in the windows and on the shop floor.

Arthur: Yea but they were like painted screens that doubled as a fashion thing, there was a Christine Schmidt collage, maybe a poster, with painting around it.

Audrey: Like a changing room?

Arthur: Yea I remember they had little feet on them, they were freestanding and you could see both sides of them. I guess it was a bit of a mix between painting and fashion design. I later repurposed it during my study at Sydney college of the arts and I painted a self-portrait with an exaggerated penis over it.

Audrey: Did you feel emasculated by your gorgeous and talented wife or was it the fashion business more generally?

Arthur: Noo, that painting was a response to some work I’d done in the shared studio space with post-grads. I’d done a rough drawing of a Penthouse centrefold. A girl I knew, who later became a Penthouse Pet. She complained, so they came and spoke to me and asked me kindly if I could take it down.

Audrey: Lovely. I think this is also the beauty of the title. It is just as much about wounded egos as the works themselves being damaged. Being sold this promise of success only to find it unattainable. It’s a bit butt-hurt in a very male painter kind of way but it also says something about the nature of desire and its entanglement with capitalism. At least the Penthouse Pet presumably made some money. I can relate to all parties.

Arthur: Artists need to take themselves out of their responsibilities to concentrate on their work. Sometimes that’s being devoted to work and selfish in other respects.

Audrey: Sacrifice, sacrifice, sacrifice.

10-03-23

Audrey: Another one of your paintings in this show, Mardi Gras, is a representation of your first ever Mardi Gras in Sydney in ‘84/5. I see every character in this painting as you. Bit Jungian. What was your experience of it?

Arthur: I was fascinated by the bacchanalia of it all, the extravaganza, the show, the theatre, the humour. I hadn’t seen anything like it before. But I also felt how it could’ve been a mediaeval festival in some way. Floats of outrageous costumes. A lot of my figurative work is self-portraiture, finding out where and how I might fit in. I always felt like an outsider but not enough to fit in with the real outsiders.

Audrey: Who are the real outsiders?

Arthur: I don’t know, the extreme performance artists who would suspend themselves from hooks or something. Painting is traditional and 2D. It’s not a couple of bricks on the floor or bottles of urine, which frankly, I became cynical about.

25-03-23

Audrey: If the real outsiders are performance artists and like Duchampian conceptual artists, do you think outsider-dom is medium specific? Is it a choice?

Arthur: I think outsider art includes the concept that these people are not fully functioning as artists. Outsider art also includes people who are mentally ill.

Audrey: So not far from the truth?

Arthur: Guess so.

Audrey: You said I was mental the other day.

Arthur: Me too. As I’m sure you’re aware… Also it’s a lack of technique. A lack of formal training. I did go to art college. I wasn’t outside the system but I didn’t particularly want to be inside the system either. In terms of medium I think painting and drawing are probably the most common for outsider art. In terms of choice, it’s a passive choice if you’re like me in that you’re not proactive in trying to forge a career as an artist. Trusting in serendipity. Which, of course, didn’t work out.

Audrey: So you’re on the outskirts of insiderdom?

Arthur: I suppose so. That’s a good way of putting it. I think the more successful artists we know like Claire Lambe, who we’ve known since the ’80s, would consider me an outsider artist. A hobbyist. I feel like I act conservative around outsiders and “outsider” when I’m around conservatives, so I don’t feel like I fit in either place. There’s some sort of rebellion there.

Audrey: Same. Thanks for that. I would say that makes us the real outsiders.

10-03-23

Audrey: Michael loved the New York School of painters like Gorky, Pollock, Rauschenberg and I see Kurt Schwitters’ influence, but these works are distinctly “Australian” to me, moreso “Brisbane”. I think that’s because he was inspired by the shapes, markings, and advertising he saw in the city’s architecture and streets. He used found house paint, spray paint, and re-combined newspaper clippings, particularly headlines, in a very postmodern poetic sort of way. What was your experience of his approach to art making and its relationship to place?

Arthur: Michael was fascinated by bizarre headlines or just a coloured bit of plastic floating down the street because of its brightness. He was horrified by tabloid newspapers, but was also amused in a free-association dadaist sort of way. Billboards, bright coloured packaging, the pop of commercialisation. In the mid to late ’70s, there wasn’t much happening in Brisbane. There were obscure punk house shows, there was the corruption of the Bjelke-Petersen government, contrasted with a suburban conservatism that could be mind-numbing. You had Rock ‘n’ Roll George cruising the streets. He was a mysterious dude in a FJ Holden dressed up with fringes and tassels and accessories. He was an institution in Brisbane.

Audrey: Brisvegas baby. There has been the fear and loathing element on this trip too.

Arthur: Yes.

Audrey: I see similar influences in your work, but in a more figurative way. Inspired by the people you saw in the streets and spectacles like Mardi Gras, protests and Big Media moral panic, mostly in Sydney. But also, this was around the exact time Bad Painting became a thing. I see that influence very strongly in your work and also in Michael’s portraiture. Did you know what that was at the time? News from New York?

Arthur: I was very disconnected from what was happening in the art world. I had studied art history, of course, and knew all the big names but it was like I stopped looking at a certain point and retreated into myself. I was trying to find some sort of primitive, visceral expression, not dissimilar to the German expressionists of the ’20s and ’30s. Max Beckmann was a hero. You know, back then, I don’t think I got Michael’s work and I don’t know if he got mine. I used to come over to this house, to his studio, next to his mother’s potting shed, and we’d talk about art and smoke joints. We were both in love with art and the process of making it. You go to art college, fall in love with painting, dream of being discovered and actually making a living out of the thing you love doing. But some of us are hopeless at taking any practical steps towards getting shown. We were an unlikely pair because I was kind of a surfer and he was not like that at all, but we connected, and that’s how I met Christine.

Audrey: But you have been discovered! I’ve discovered the foremost underground artists of Brisbane. Now that we’ve resurrected these works, for their first and perhaps last exhibition, how do you feel about it? Do you think Michael would’ve liked it?

Arthur: I am happy to be having a show with my mate Michael and my wife. I think Michael would have been happy to have a show because he always dreamt of having one and he continued working, producing, over-producing, until the very end. And I love these works of his. I’m sad he can’t be here to see it.

25-03-23

Audrey: What did you think of the way I curated the show? I know you were desperate to clean all the mould, white ants nests and dust off everything, so thanks for abstaining.

Arthur: Yea look, I got what you were doing, but I did wonder if it was a bit “trick”, like a gimmick. And I would have liked to have seen my paintings clean, in the colour that they were. I also didn’t think people would want to buy them if they were mouldy and rotting. But I get the idea of it being an archeological dig, paintings exhumed from the tomb.

Audrey: For me it was more about the almost-too-perfect situation. These works of Michael’s that use word-play like WOUNDED CAR PARK! and THIS HOUSE and SUNDAY (which I’m now reading in terms of being a Sunday Painter), were literally “discovered” “underground”. Damien Hirst had a ridiculous budget to do “Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable” in Venice — where he painstakingly fabricated the “discovery” of a lost civilization in an abominable install that took over the sinking islands. There was also that artist who submerged a dress in the Dead Sea for two months so that the salt crystallised around it. Essentially people spend a lot of time and energy to make something look older, or to collaborate with natural forces. In this situation, the mould, rot, termite nests, dead bugs etc. are actually the work of 30+ years of careful neglect.

It’s much less gimmicky than something like the Hirst thing, but I suppose wanting to give you (and Michael posthumously) the thrill of being “discovered” is a trick in a linguistic sense. There is a sadness, about dreams barely fought for and lost, but there is a sort of horrific pleasure in making these works “undead”. Something beautiful about the paint flaking, the mould taking over, the masonite disintegrated by termites etc. Something satisfying about installing with the plethora of hoarded materials we found in the house (the curtains, pulley hooks, eye hooks, hammers etc.) We sold pretty much every painting didn’t we? They live!

Arthur: We did. I was so happy that our works have a new life. One couple came with protective gear to carefully clean their painting before they took it away because they were worried about getting sick. Meanwhile we’d been working in that mould and dust for weeks.

Audrey: And sleeping in that black mould dungeon on damp single mattresses side by side like inmates when we were setting up the show. Honestly, this is outsider performance art. The artists are present and now have asthma and ptsd. I don’t know how we survived each other.

Arthur: We were thrust into close quarters and it was difficult. Because of the heat, the humidity, all 80 trips to the dump. It’s amazing we didn’t kill each other.

Audrey: I wanted to.

Arthur: I have a question for you. In what school do you see our work? Is it the New York school? Is it specific to that time? Is it relevant now? What’s the genre?

Audrey: I don’t know, I’m bad with genres and schools. I guess it’s postmodernism? I’m always more interested in where art sits contextually, to try to understand what it is responding to or in dialogue with. So yes, I think it’s of its time, and place. You said you saw The Saints play at art school and there was this specifically Brisbane punk attitude. The ’70s saw the deterioration of the Peace and Love energy of the ’60s and then you hit the ’80s, which was turbo coked up hedonism/capitalism. I can see this pushed up against a sort of small-town psychogeography in Michael’s work. A bit of a situationist element. And, although I hadn’t seen any of Michael’s works at the time, Alethea Everard’s show at Meow2 (RIP), Art Show (2020), was stylistically very similar. But different, it’s of its time and place too.

I do think that the way I curated this show is specific to the present moment, so it takes it “out of time” a bit. To me it’s not just nostalgia or like nepotism (although I do long for the nothingness before I was born and a career supported by my family), but like the classic morgue scenes you find in zombie movies, where the corpse’s toe, with its little identification tag, twitches before the body springs up and starts hunting for brains or something.

And I already talked about Bad Painting, so I guess the zombie element also makes it bad (worse?) taste, giving it some c-grade movie energy.

Arthur: Taking the piss.

Audrey: Yea.

Works by Arthur Schmidt, Christine Schmidt and Michael Lynch

Curated by Audrey Schmidt

Documentation by Phebe Schmidt

All works and materials found in the home of June Lynch (1932-2022).

This exhibition took place on unceded Turrbal and Jagera land. We acknowledge Elders past and present, and the rich ongoing histories of art making that have thrived in so-called Australia for over 65,000 years. Always was, always will be, Aboriginal land.

Details

Acknowledgments (as though I’ve written a book):

- Huge and warm thanks Rory Mason for helping me install, letting Glenn boss you around, dealing with the intensely dysfunctional duo of me and dad and making sure I got out for beers.

- Thanks to Glenn for being trigger-happy with the nail gun and forcing us to make decisions. I enjoyed the Northern Irish commentary and I know my grandfather from County Cork would sadistically enjoy that his giant and imposing portrait now hangs in your house. Kind of like the story you told me about your great grandfather who was buried standing up because “as long as there are catholics…”

- Thanks to Neil and Julie for doing all the trips to the dump for us.

- Thanks to Gordon Hookey for coming and bringing Josh who jumped straight into Milani gallery assistant mode and made the whole thing seem much more profesh.

- Thanks to Rohan and Sig for your emotional support and for really selling Brisbane back to me.

- Thanks to Phebe for documenting and coming up for a sunny coast weekend.

- Thanks to Guzzler, Meow and Liam Osborne for everything.

- Thanks to people who bought stuff.

- Thanks to Dad for doing the heavy lifting with me.

- Importantly, thanks to Mum for letting me do this show even though the house is the source of so much pain for you. Love you.

- Mum and Dad, thanks for sacrificing your art careers to be parents even though I definitely never asked to be born. I am grateful that you are such a rich source of material on so many levels. Writers with normative family and social lives always seem to be so strapped for content xx

-

The house belonged to June (AKA Gemma) Lynch (née Eunice Clemm), who passed away in October 2022. Mother to my mother, Christine Schmidt, and her brother, Michael Lynch. She chose the name Gemma in the place of a pet name for elderly relatives. Eunice is her dead name, June is her chosen name. Lynch is her married name, but she kept it after she was divorced around ‘86. Throughout, she is referred to as both Gemma and June. ↩

Cover image: Michael Lynch, Unknown (Tonight), detail, c.1977-85, mixed media on masonite, vacated termite nests and tracks. Photo: Phebe Schmidt.