I recently discovered I was born under the malevolent star Algorab. Like most stars observable without high-powered telescopes, its name is ancient, derived from the Arabic meaning “the crow”. This is in reference to its dark glimmer and the gifts of craftiness and subterfuge it is said to lend those born under it. Discovering that my ruling planet occupies a place of mendacity was data I initially found disconcerting, not quite confirming what I know about myself but not totally untrue either. It settled into my mind like sand through water, at first cloudy; but then—another layer. It makes sense.

The discovery was one of many peppering my return to astrology as a sort of lockdown time-suck, following an impulse to find out exactly, mystically, what was wrong with me. As I entered the popularly notorious transit of another dark star, the period around 27-30 called the Saturn return, I wanted to take the reins from the horoscopes of Susan Miller and others that I had previously relied upon for sometimes misfiring insight. I read horoscopic reports for years as a way of gaining self-knowledge and something like agency. It is easy for me to register a selfish impulse in their appeal, a sort of cosmic narcissism confirming fate’s vicissitudes as they relate to me. But there is also something else, some hungry locution that tessellates like poetry about the depths of what is—in general, not just for me.

This is the same pull I recognise operating on peers in the weird resurgence of astrology over the last few years. It appears to have surpassed the just-for-fun framing that seemed to characterise it when I was growing up in the 90s and early 00s, ascending to epistemological seriousness in the wake of new waves of spirituality and the internet’s removal of access barriers to formerly esoteric or marginal fields of thought. Astrology is increasingly treated as a vital stream of data among many others, intersecting with trend forecasts, political analyses, family planning and crypto investment with equal gusto. It has expanded, amoeba-like, to conquer both the cosmic left and the cosmic right; the most cynical zoomer insight memes as well as toxically wounded yummy mummy wellness discourse.

If finding the capacity to process unprecedented information flows is now a necessity, astrology can be seen as archetypal of the data-for-the-sake-of-data repost culture that grips our current moment. As Emily Segal argues, this can be further refined to the astrological phenomenon of Mercury retrograde, when the planet of communications appears to move backwards in the sky, heralding travel delays, technological failures and bungled messages as it does so. Writing during the first flush of the current wave of astrological popularity in 2016, Segal takes the already-passé fear of Mercury’s backward motion as a paradigm: not just as the most accessible belief-meme of the way astrology operates in the world, but also as an apt description of the global information economy it circulates within, one that is in constant, crisis-laden glitch.1

While it’s no longer news that astrology has gone mainstream, it’s still true there is a distinction between the way that it popularly circulates amongst lay people and its actual implications as a system of poetic insight. Shifting from Co–star notifications as a primary source material to serious astrological texts dealing with whole charts and calculation techniques is also just a shift in the sorts of filters and rubrics that need to be applied to receive and interpret its multidirectional information. It’s all just processing, which can seem baffling to sceptics and outsiders who assume that almost all astrology is cold-read from the stereotypical ether. For these people, the marketing of astrology is the thing that is foregrounded, leading to the belief that astrology is nothing but marketing, content concomitant with its context. For those a little further in, we realise that there is an independent mechanism at work, but what is it, if not another proliferation of desire and data?

Divination

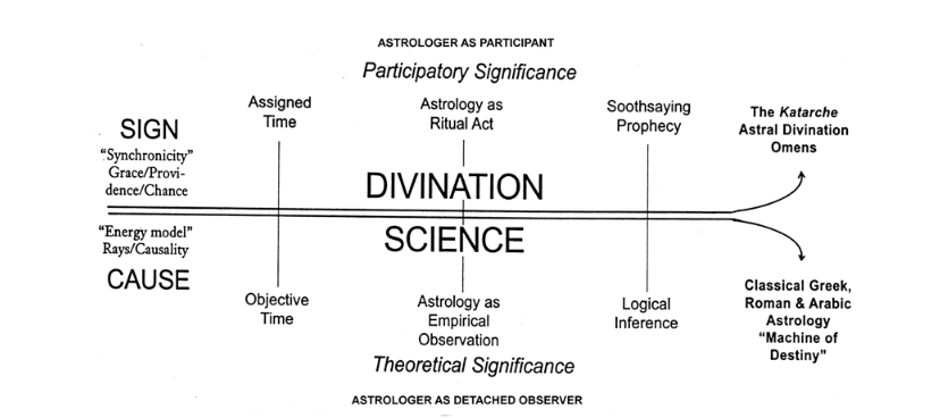

Although there is confusion and debate surrounding this point, astrology is, fundamentally just another form of divination: like tarot, like tea leaves. This may be surprising for those who assume its causality to be rooted in some vaguely defined planetary “influence”, in the same way that the Sun controls the seasons and the Moon the tides (and did you know that our bodies are 70% water?) There are even practicing astrologers who reason in this way. Such a logic seems intuitive, supposing that astrology works because celestial bodies, even those further out with minute earthly visibility and gravitational pull, emit energies that affect how we feel and act in this world. But it is a historically contingent logic. As Geoffrey Cornelius points out, the “why” of astrology has strategically shifted from its uncomfortable beginnings in ancient religion and into whatever is the prevailing science of the day.2 Natural philosophy was followed by humoral theory, gravity, magnetism, radio waves, depth psychology, and most recently quantum physics. These are scientific frameworks that provide a pretence of rationalism to cloak the actually quite irrational operation of divining from the planets.

The fact that such reasoning prevails, both amongst lay people and actual practicing astrologers, can be contextualised within the various historical hegemonies of Greek philosophy, Christian monotheism and post-Enlightenment rationalism that the tradition has survived within. Its post-Copernican relegation to one of the “wretched subjects” is rooted in an epistemological climate that institutionally rejected divination as unscientific because unprovable. Astrology still elicits a strong emotional reaction among contemporary academics, scientists and sceptics.3 It is no wonder then, that science continues to be the decisive language of its justification, just as individualism has become its most common inflection. The strategy has sometimes been enough to save astrology from being cast as straight-up fortune telling and targeted in historical legislation and purges, but has also left the discipline open to basic astronomical critiques that regularly surface—for example, professing new or alternative sun signs due to the precession of the equinoxes.

Astrology’s obfuscation as divination is helped by the maths and empiricism at the system’s core, which seem to differentiate it from other forms of plumbing the depths. The mathematical component of astrology also means that the system’s abstraction into scientific language has been more than just strategic: it is also an extension of the foundational abstraction that makes a “birth chart” possible. As a systematised calculation of observance, where each of the planets and stars have been assigned meanings and mechanised via their perceived positions relative to the Earth, the chart is partially removed from the divinatory premise that sees, for example, a creepy blood moon eclipse and surmises the impending death of the king. It feigns objectivity through complicated math that makes it seem more than the subjective interpretation of visceral experiences in nature.

But the spiritual element of astrology is remembered in elements such as names of the planets, taken from the classical Greek gods because they were originally thought to be their direct emissaries.4 Divine omens indicating events on earth have always come in the form of natural phenomenon—an eagle with a swallow in its mouth, for example5—and using the movement of the planets and mapping parts of the sky is a way of sealing these omens within a symbolic system that ensures a constant and collectively observable stream of omen-based symbolism. This “Machine of Destiny”, as Cornelius terms it, is reflected in the functions of the earliest computers such as the Antikythera mechanism and astrolabes, which are principally tied to systemic sky observance. Other forms of divination, like the 78 traditional tarot cards, the I Ching, or Wikimancy, rely on similar forms of abstraction via human-made texts and visual systems. But none is so effective as to be able to integrate mechanised time and actual natural occurrences into a chartable, navigable and almost-infinite clock.

Psychology

The robustness of the astrological system is of course core to its appeal, both now and in the past; it is a clock that spins backwards past capitalism and on through environmental Armageddon. Astrology’s ability to speak to personal experiences as well as political realities have cemented its ineffable and incorrigible continuity as a cultural force across civilisations. In late capitalism it occupies a space that Theodor Adorno called a sort of “psychological twilight”, the gap between modern, rational subjectivity and premodern superstition.6 With the dogma of rationality only strengthening through the last century, most of the effects and perceived benefits of astrology have naturally found host in psychology and therapy, fields that bring science and individualism so consummately together.

This is in large part due to the influence of one of astrology’s last great defenders able to parse the demands of the discipline with the demands of the academy: Carl Jung. In the decades following his death, Jung’s work has proliferated not only within institutionally sanctioned psychoanalysis and cultural studies, but also in astrological practice.7 Contemporary Jungian analysts sometimes frame astrology as valuable in its “compensatory” function, an irrational respite from the exactitudes of ordering one’s life and emotional world according to the mores of rational modern subjectivity. Meanwhile the Jungian approach to astrology emphasises astrological archetypes as forming part of the “collective unconscious”, moving through the chart as they move through myth to influence our experiences and understanding of them.

In a way, psychological astrology tacitly accepts the divinatory premise of the system as a symbolic language in excess of reason, but it also often restricts astrology from making predictions or even descriptions of concrete events. In this kind of astrology, Mars in the fourth house is more likely to signify masculinity issues than it is to herald a house fire. The irony is that this is a narrower application than Jung himself adhered to. He understood astrology as a form of synchronicity: an acausal, meaningful connection that is simultaneously “numinous”, meaning it contains an element of the divine. The definition sidesteps science in eschewing “provability” as a validating rubric, walking the fine line of claims that are rationally permissible to espouse in its reference to the spiritual. Synchronicity can approach the twilight of the rational mind as Freud did, through dreams, but Jung’s model provides a framework that also allows for access to an unconscious that is more broadly defined, bridging the individual with the shared physical universe.

The most famous instance of synchronicity Jung records doesn’t focus on astrology at all, but an earthly omen. He recounts one of his clients, a young, educated woman, telling him about her dream the night before, where she was gifted a golden scarab beetle. He hears a tapping at the window of his dark office on the shores of Lake Zurich, opens the window, and to both of their surprise a golden beetle, “the nearest analogy to a scarab one finds in our latitudes”, flies in.8 The episode is meaningful because the woman had been struggling to find a way of dealing with her emotions in a way that squared with her institutional education. The physically manifest sign, in its glinting gold and natural splendour, is permissive.

Wellness

The connection between the literal interpretation of signs and their psychological significance is what makes astrology so enticing as a response to crisis, both personal and political. Framed this way, the current resurgence of astrology has taken place within the glitchy geopolitical spiral that has seemed to characterise the last few years, not least—in astrological terms—Saturn’s movement into the social, societal air sign of Aquarius in March 2020 and the widespread transmission of this socially-restrictive respiratory virus. Along with magic, which has also undergone a resurgence, the revival of astrology has been fomented by crises and precarity that form a fertile breeding ground for alternative belief, demanding personal agency and insight where their lack has most often been foregrounded.

The current popularity of astrologers that unify political concerns with individual wellness is characteristic of this dynamic. Among them is humanistic astrologer-cumcounsellor Jessica Lanyadoo, who started her now-cultish podcast in 2018 explicitly because she was concerned about the disastrous alignments of 2020. Lanyadoo coaches her listeners on traditional astrological topics like love and money in a way that is compelling but also deeply tenderqueer and fragility baiting, tapping into the “queer witch” phenomenon in a way that is broadly accessible. She also dwells on ways to optimise responses to social upheavals and contributions to justice movements while maintaining personal integrity and warding off burnout. I listened for a while when I was depressed in the middle of the first round of lockdowns, until I realised that almost every transit she described seemed to signify a harshly intense collective mental health episode.

This gets at the danger inherent to the divinatory principle: that it is interpretive. Multidirectional assonance can slip quickly into vagaries, and people (astrologers included) can say literally whatever they want. If the current astrology boom is located partly in the demands placed upon us in late capitalism, astrology is enticing because, as Tabitha Prado Richardson posits, it is expansive enough “to carry both optimism and pessimism depending on emotional necessity”.9 Even after deciding I would stop listening to the pod while scheming, doing admin, or supplementing social contact, after I had started to learn astrology and discovered some of the alarmist sentiment was pretty unfounded—I found myself returning to listen out of the sheer comfort of vaguely “knowing what was up”. The data was flowing. This brings us back to Adorno’s analysis, that astrology doesn’t need total adherence in order to do its compelling work. For most consumers, it simply suffices to “get the dope”.10

Dope

Adorno’s rancorous piece aligns astrology with his view of Hollywood and other forms of media selling a dream: as nothing more than a series of psychological hooks exploiting contemporary experiences of alienation. The object of his study, Carroll Righter’s LA Times horoscopic column, can have no factual basis and so merely takes advantage of feelings of powerlessness among those who are structurally excluded, or simply not intelligent enough to grasp the way that power actually moves in the world. This not only connects astrology, presciently, with witchcraft—a last resort of women, queer people, poor people and ethnic minorities—but also with a sort of flatearther or QAnon-style “truth reveal”.

Conspiracy theories are the domain of the unintelligent because they replicate the heady gestures of exposure that have characterised modern intellectualism, what Paul Ricoeur called “the Masters of Suspicion” and Eve Sedgwick “paranoid epistemologies”.11 Adorno’s phrase, “prophets of deceit”, speaks more to the way in which insight itself is commodified and circulated in popular media.12 Another term might be outrage. Denouncing the puppet masters, be they transsexual cabalists or out of sect malefics, always seems more intelligent than it actually is, because it gives the illusion of interpretive agency and special insight while flatly dramatising the loss of control to mechanisms larger than the adherent. This is why Adorno identifies astrology with the still-present threat of fascism, because, on the face of things, they share some of the same psychological motivations.

This is a sinister lens indeed for viewing the recent rise in astrology’s popularity, forming an irrational, woke-seeming mirror to the fascist movements that are also in resurgence globally.13 Adorno warns that in its dramatisation of systems of control, insinuations of fear and emphasis on optimisation, astrology ultimately marks the “transition of an educated liberal ideology to a totalitarian one”.14 Like fascism, it proliferates messages from on high covering every conceivable topic of life, advising how best to self-regulate and succeed under current circumstances, while regimenting all pleasure into either cosmically-permitted ecstasy or endless readjustments of labour. Most sinister of all, astrology justifies itself not only as a science, but also as a return to the past and ancient systems centuries in refinement, just as fascists advocate a reprise of eugenics and a fictional racially homogenous past. If we follow Adorno’s line, this is all trickling into our consciousness every time we read that menacing little paragraph next to the stylised glyph belonging to our sun sign.

Power

The fact that the current astrological renaissance has been spearheaded in large part by women who are young, queer and of colour, and its nearest legacy is most stereotypically espoused by older hippies, perhaps obscures its lineage as a system transmitted via the pens of mostly ruling-class-adjacent men.15 The Reagans, the Nazis and J.P. Morgan all turned to astrology, just as ancient rulers used it to plan warfare, power grabs and acts of violence. Its image as a trapping of the young left is only recent, and perhaps has more to do with the terrain of the culture wars in which we currently find ourselves. The crisis of liberal ideology that became most apparent through the 2010s can be contrasted with a new form of liberalism that, in a certain sense, has already begun integrating astrology into its worldview.

“Disguised” forms of astrology have circulated for years, perhaps most significantly in the (now waning) popularity of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. The personality test was based on Jung’s Psychological Types (1923), in which he used the elements of astrology, the triplicities, to describe his patients. Katherine Briggs and Isabel Myers used this to formulate an independent system of archetypal assonance that has found use in everything from dating apps to corporate human resources. Today it’s like these soft takes, or even people being cagey about their astrological adherence in casual conversation, have been dispensed with. Some companies now openly filter candidates based on star sign to balance office dynamics, just as some tweaked sharehouses do, in what has been dubbed in certain outrage pieces (and a strikingly ironic turn of the astro data industry) “astrological discrimination”.

Sun signs obviously do not have the same structural consequences as other kinds of identity, and yet, as a form of categorisation that depends on a certain level of collectively-upheld magical thinking, astrology can be productively compared to race.16 Ancient delineations for planetary configurations, like their twentieth-century counterparts, create and maintain value distinctions that favour strong men and lightness, resource extraction and productivity, often denigrating foreigners, angry women, drug use and sexual nonconformity. Because of the influence of archaic male-authored sources (Ptolemy, for example), interpretive precedents often look back to an idealised GrecoRoman past in which the man was a self-governing entity, keeping his slaves in the 6th house of his chart.

The astrologer Alice Sparkly Kat and author of Postcolonial Astrology (2021) says that, due to the nature of its lineage, astrology is like whiteness in that “it makes itself visible when certain sociopolitical relations are under threat”.17 Evil historical figures used astrological insights to supplement fantasies of maintaining power, or to justify their claims to divinely ordained supremacy. The Roman emperor Augustus published his apparently auspicious birth chart as propaganda to bolster his reign, and Goebbels hired astrologers to fabricate predictions of the “Thousand Year Reich”, after scouring Nostradamus for the same reasons.18 Whether these figures and the regimes they represented actually put faith in astrology is irrelevant (both carried out purges and execrations on astrologers and fortune tellers)—they recognised its power in commanding an iconic sort of legitimacy through the production of persuasive media content.

Advertising

Segal’s work on Mercury retrograde began with a previous project called K-hole, a trendforecasting collective that published a series of trend reports as art texts engaging the commercial form. The 2015 Report on Doubt articulates magic as an “organising principle already in operation in our world”. It is a read on astrology: “We’re talking about magic, not wizardry. People believe they are Slytherin; they don’t believe they can fly on brooms.” The point seems to be that identity formation through commercialised categories, like those offered by sun signs, are a primary vector for contemporary experiences of the numinous. Belief runs quickly into purchases stamped with preternatural significance through the easy branding of typologies that offer the depth of characterisation to people, places, moments and things. The commercial use of astrology is evident around us, in designers offering twelve different star sign necklaces or bags, or the division of personality types into Sailor Moon characters, each with her particular lip gloss shade.

I was reminded of this effectiveness a few months ago when the Australian Health Minister Greg Hunt announced that 70 percent of the population had been fully vaccinated. He went on to specify the figure more precisely: 70.007 percent. “It’s a memorable number,” he said, “but it’s memorable above all else because it represents the movement at a national level to phase B of our national roadmap.” While regular exposure may have us accustomed to barky jargon issued from the mouths of Canberra’s ad men trying to convince us they’re morally coherent and on top of the pandemic response (they’re not), the open recognition of the lucky-seeming potency of the symmetrical number was striking.

The connection between astrology and advertising can also be located in the system itself, which is cultish, inexhaustible, containing a strong desirous pull evinced in astro Twitter and Tiktok accounts with millions of followers. For K-hole, magic and branding are both concerned with inception, like divining from the time and place of birth. “But where branding is about implanting ideas in the brains of an audience, [magic] is about implanting ideas into your own.”19 In the “prosuming” economy this line is pretty blurry, a fact that is a precautious bit of salt for those reading this thinking I’m saying that advertising is “bad”.

While advertising is often deployed by corporate or governmental entities that do not serve us, there is agency in this kind of inceptional magic: it can be used on others or on yourself, and it is often used collectively. This is what makes astrology so powerful as a vehicle for not just information, but also for affect, a kind of epistemological labour. It is a tool for manifestation, a “science that doesn’t split subjectivity and objecthood”, for better and for worse.20 But, as the byline of K-hole’s trend report points out, “seeing the future ≠ changing the future”. Accessing agency against structures of power that attempt to monopolise various forms of magic and mysticism remains a problem.

Novel

The reparative element I see in astrology even while knowing so much of the wellness and mystical industries are toxic comes back to a faith in the power of narrative. For years before I was able to read birth charts, I read tarot from decks that also contained within them legacies of violence, puritanical Christian values, colonialism and gender hierarchies—and got a lot of personal growth out of this that didn’t necessitate thousands being spent on therapy (which I couldn’t afford at the time anyway). I also read novels, which were tools for gaining self-knowledge before anything else. Segal’s development of her original e–flux piece into a novel, also titled Mercury Retrograde (2020), thus felt something like the closing of a circuit when I got a copy. It test the limits of divinatory agency and “reading the world” in a way that is both depressing and deeply gratifying.

Segal’s novel pits the efficacy of omen-interpretation against the context in which the protagonist Emily lives and works, pre-pandemic New York City and a toxic tech-bro startup with views to being tastefully radical. It uses divination as a sort of horizon of understanding that structures both the plot and Emily’s decision-making. She chooses to sell out of the art world proper and into the start-up following a session with an aura reader called Riva, reasoning that the move will be an artistic gesture towards creating new manifestations in the world transcendent of corporate efficacy. “I believed it was possible to do [this] by design: creating logos, T-shirts, parties and schematics that overflowed with personal richness, disguised as mere brand differentiation”.21 But rather than taking control of the data she is enlisted to create and market, Emily seems to drown in it.

Like astrology, the company’s purpose is in layering new information over existing information, creating a stratum of meta-language that covers every conceivable topic, “a map as big, or bigger than, the territory” it claims to represent.22 It doesn’t directly turn a profit, but secures exorbitant amounts of venture capital that is used to produce networks of data and disseminate the brand in campaigns that enhance the company profile and that of its founders. “Life itself is meta”, one of the boys repeats, as the vehicle they have created for their own success propels them into new personal wealth (“richness”) that Emily only has subjunctive access to. Things obviously turn sour, despite her attempts to discover direction and take control via the signs around her: dreams, cards, articles, artworks, sweatshirts, significant asides and bodily phenomenon.

The novel is a roll call of divinatory principals, signs that are correctly interpreted or not: “the whole tarot of life, laid out and ready to be read—but you don’t read it”.23 The institutional force represented by the male founders and their company is impenetrable, and they end up beating Emily at her own game, creating an artwork incorporating the sigil-esque company logo that technically “cost hundreds of millions of dollars to make”, inclusive of Emily’s salary.24

Her response is to resign and implicitly tap out of the interpretive logic that was feeding her attempts at finding agency. The novel’s typological and symbolic vision sort of dissolves towards the end to see the founders as flat social actors, just people mechanistically doing what people do. The boys’ faces seem to erode for Emily, in personal pain and inexplicable featurelessness, rupturing the “pareidolia” the novel dwells upon in a chapter on face-like logos: the human tendency to recognise schematic patterns in otherwise meaningless stimuli like rock faces and automobiles.

Fish

Segal’s divinatory pessimism is relatable to the times that many astrology practitioners will have experienced: when interpretation goes wrong, or when it reaches the limit of what it can give. The novel reminded me of another novel subliminally structured by divinatory principals, W. G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn. It begins,

In August 1992, when the dog days were drawing to an end, I set off to walk the county of Suffolk, in the hope of dispelling some of the emptiness that takes hold of me whenever I have completed a long stint of work. And in fact my hope was realised, up to a point; for I have seldom felt so carefree as I did then … I wonder now, however, whether there might be something in the old superstition that certain ailments of the spirit and of the body are particularly likely to beset us under the sign of the Dog Star.25

Sebald’s narrator collapses on the first day of his walk, partly overwhelmed by the deep, historical traces of destruction he finds littering the countryside, and partly by a vision of himself like Gregor Samsa, transformed into a cockroach crawling on the face of the earth. The information is too much, and the stars too harsh, it seems, for him to continue—and yet he does.

The narrator’s walk resumes and the remainder of the book details a disarming string of (acausal, meaningful, numinous) connections related to the ongoing traces of physical and environmental ruin, wasted lives and love lost he finds in the landscape. The deluge of details spanning, for example, the rise and fall of Empress Dowager Tz’u-hsi (Cixi), drowned US fighter pilots and the former name for Sirius, the Dog Star, in Osiris, is sometimes dizzying, broken only by images and brief mentions of the journey’s practicalities. One chapter typifies of the effect of the novel itself, detailing the North Sea herring population where “untold millions […] rise from the lightless depths” and fill the shallows of the Suffolk coast in sometimes unwanted, suffocating layers. It seems a fitting metaphor for divination, literally plumbing the depths to release a potential glut of information that tends to rot in times of plenitude and in times of dearth starve out those who rely on it. The dead fish glow in the dark, while in bumper years their scales shimmer on the surface of the water, “resembling ashes or snow”.26

“Hello from below” is a recognised shorthand for divination that draws on the symbolism of a fish rising from the deep as a sign from nature.27 Catching a fish is about possession, taking what is not necessarily given, and not necessarily wished for. As a metaphor it also draws attention to a certain filtration mechanism that attempts to separate certain stimuli out as meaningful while relegating other details to obscurity; the fickleness of what you catch and when is dependent on both the tools at hand and the unseen actions of fate. The divinatory moment is fundamentally about the characterisation of time through the specificity of what information surfaces, when and how it does so. Sebald’s herring chapter also details the deformities and morbidities in the herring due to industrial pollution now seeping into the Dogger Bank.

The Rings of Saturn and Mercury Retrograde are alike in that they dramatise the ability of divination to shape narrative as well as the ability of narrative to shape divination. They both highlight a problem inherent to the circulation of astrology in the contemporary landscape: that its attempts to characterise identity, things and time itself, are participatory with the deep contestation of these things as they are collectively redefined in ongoing violence and crisis. This, I think, is the other driving factor in astrology’s current popularity—that like other forms of divination, it is a form of epistemological labour that has a thrilling but perilous tendency to backfire on those who seek to substantiate it too concretely. Astrology outsources forms of intuition that might otherwise be experienced in the specificity and limiting circumstances of the body into an external and abstracted framework that taps this same potential. It may not be a science but, like advertising and fishing (and tarot and tea leaves), it is a form of technology.

-

Emily Segal. “Mercury Retrograde.” e-flux Journal, August 28, 2015. http://supercommunity.e-flux.com/texts/mercury-retrograde/. ↩

-

Cornelius, Geoffrey. “Is Astrology Divination and Does It Matter?” Centre Universitaire de Recherche en Astrologie (C.U.R.A), May 22, 2000. http://cura.free.fr/quinq/01gfcor.html. The diagram is lifted from its first publication in The Mountain Astrologer, via Cosmocritic’s publication: http://www.cosmocritic.com/pdfs/Cornelius_Geoffrey_Is_Astrology_Divination.pdf ↩

-

“Strong emotional reaction” is from Helena Avelar, see Luis Ribeiro and Chris Brennan detailing her life and work on The Astrology Podcast, ep. 324. ↩

-

Ancient astrology was first developed in ancient Babylon and Egypt, meaning the stars (aka planets) were originally assigned names of deities belonging to those cultures, with significations that were imported and combined with Greek counterparts. Venus was Innana in ancient Babylon, with a myth detailing her journey through the “underworld” as she is doing in retrograde as I am writing this: going behind the sun to change from an evening to morning star and losing her garments as she does so. ↩

-

The omen at the end of Homer’s Odyssey. ↩

-

Theodor W. Adorno, “The Stars Down to Earth: The Los Angeles Times Astrology Column: A Study in Secondary Superstition,” Jahrbuch für Amerikastudien 2 (1957): p. 25. ↩

-

Most notably through the work of astrologers Dane Rudhyar, Steven Arroyo and Liz Greene. ↩

-

Carl. G. Jung, “Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle,” Trans. R. F. C. Hull, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1973: p. 31. ↩

-

Tabitha Prado Richardson, “Who Needs Astrology?” The Lifted Brow, November 17, 2019. https://www.theliftedbrow.com/liftedbrow/2019/11/10/who-needs-astrology-by-tabitha-prado-richardson. ↩

-

Adorno, “The Stars Down to Earth”, p. 22. ↩

-

See Sedgwick’s essay “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading, or, You’re So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Essay Is About You,” (1996) and Ricoeur’s Freud and Philosophy (1965). ↩

-

Adorno, “The Stars Down to Earth”, p. 81. ↩

-

While I was writing this my favourite podcast host Chris Brennan of The Astrology Podcast even mentioned the fear of this elision as a potential source of backlash against the recent rise in astrology’s popularity. See episode 331 with Adam Sommer. ↩

-

Adorno, “The Stars Down to Earth”, p. 22, 87. ↩

-

Chani Nicholas is to my knowledge the first mega-popular astrologer to bring a millennial leftist lens to the practice. Demetra George’s work is significant in delineating meanings for the asteroid goddesses in the 1970s, interpreting their discovery as attendant to the recuperation of the feminine in patriarchal culture. ↩

-

Pavithra Mohan, “From Tarot Readings to Gemini Memes, Astrology Has Officially Infiltrated Work Culture.” Fast Company. September 10, 2019. https://www.fastcompany.com/90398481/from-tarot-readings-to-gemini-memes-astrology-has-officially-infiltrated-work-culture. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

MI6 also hired an astrologer during WWII on hearing the Nazis were dabbling in a perverse sort of divinatory arms race. See Eric Kurlander, “Adolf Hitler: Obsessed with the Occult.” Historynet, March 19, 2022. https://www.historynet.com/obsessed-with-the-occult.htm. ↩

-

“K-Hole #5 A Report on Doubt.” K-HOLE, March 1, 2016. http://khole.net/issues/05/. ↩

-

The Jeane Dixon Effect and Hannah Black, “Love Homoscopes.” The New Inquiry, January 15, 2015. https://thenewinquiry.com/love-homoscopes/. ↩

-

Emily Segal, Mercury Retrograde (New York: Deluge Books, 2020), 74. ↩

-

Segal, Mercury Retrograde, 84, 85. ↩

-

Segal, Mercury Retrograde, 63. ↩

-

Segal, Mercury Retrograde, 177. ↩

-

Winfried G. Sebald, The Rings of Saturn, 1995, trans. Michael Hulse, (London: Vintage Classics, 2002), 1. ↩

-

Sebald, The Rings of Saturn, 55, 56. ↩

-

See T. Susan Chang and Mel Meleen, Fortune’s Wheelhouse, episode 49: The Page or Princess of Cups, July 2018. As a maritime symbol, the fish is fitting with the astrological reasoning for its own current popularity: Neptune in Pisces, the planet of illusion and delusion, of inspiration and divination, in a sign of watery expansion. See Austin Coppock in The Astrology Podcast, episode 329. ↩